When we talk about destruction, it’s inevitable that the conversation veers towards the subject of failure, risk and ‘unfinishedness’. In the following text, exhibition maker and writer Jo Melvin, and curator Jes Fernie, wrangle with these concepts, moving on to a discussion about touch, destruction-restitution, and the fraught, fantastic possibilities of the archive.

Jo Melvin: I’d like to throw a spanner, or rather a boomerang, into the works, to begin our conversation. This is rhetorical at its most profound. I’d question distinctions you have made in the Archive of Destruction over the potential energy within ‘unfinishedness’ – whether, or when an artwork is finished, being tied to its encounter outside – sculpture, monuments and site-specific work.

Jes Fernie: Having set up this exterior / interior (or public realm / gallery) binary, I find myself constantly wrangling with it, worrying over its slightly clunky distinction. So, I wholeheartedly welcome your rhetorical spanner! Of course, art located beyond the gallery space doesn’t have a monopoly on ‘unfinishedness’; artworks in museums and galleries can be changed in multiple ways by an encounter with an audience. But there must be a distinction between sites that people have elected to enter and sites that they inhabit as part of their daily life, and these sites’ relationship to the idea of ‘unfinishedness’. In my view, there is an additional element of possibility, agency, energy that is embedded in work sited in the public realm, due to its raw relation to many different publics and the volatile political, social and environmental contexts in which it might exist.

When Josephine Meckseper’s Untitled (Flag 2), (2018) – an abstracted US flag with what appears to be a black scrawl overlaid across it – was installed in a public square at the University of Kansas a few years ago at the height of Trump’s febrile administration, an onslaught of right-wing vitriol led to its very rapid removal and re-location to the on-campus gallery where it was considered to be ‘less contentious’. The same could be said for David Hammons’ How Ya Like Me Now? (1989) – a billboard-sized white-skinned blue-eyed Jesse Jackson – which, after being destroyed within minutes of its installation on a very public site, was remade and installed within the ‘more protected’, enclosed environment of the Washington Project for the Arts. There’s an energy and air of possibility (and vulnerability) in sites that are ‘contentious’ and not ‘protected’ that I would say, at the very least, allows for a different kind of ‘unfinishedness’ and relation to the public. All this being said, I understand that your more evocative, expansive take isn’t tied to a particular site and I like this idea of a ‘place of encounter’.

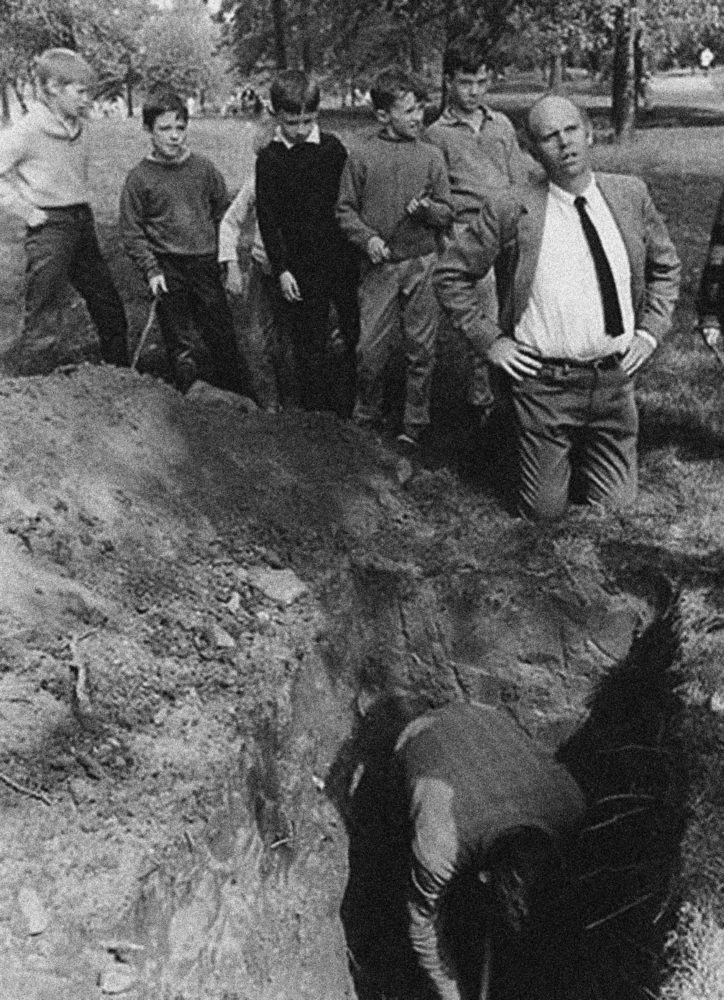

JM: Claes Oldenburg’s Placid Civic Monument (1967) – a grave-size hole in Central Park, close to the Museum of Art, was part of a wider city outdoor sculpture project. There was some funding, enough to cover costs. What continues to resonate for me is the idea of a hole dug by grave diggers as a monument. In other words, the lack of objecthood – and body! – and the fact that it goes downwards, inwards, rather than rises, as would be expected in the classic sense of the monument. Its temporary nature as a hole had, and continues to have, a durational quality, which is in itself multi-layered.

JF: This ‘digging down’ is a powerful metaphor for the anti-monument, one which works against the logic of both the market (the thing to be bought, sold, admired, rebranded, moved or controlled) and hierarchical systems (institutional, colonial, social). It brings to mind Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz’ Monument Against Fascism (1986) – a twelve metre aluminium cube that was gradually lowered into the ground as members of the public engraved, gouged and hammered their names into the surface in support of a public statement against fascism. It has now disappeared into the earth and the site is ‘empty’, its durational existence playing havoc with our understanding of objecthood, monumentality, and erasure.

JM: This hole, a space to encounter, for the viewer to project into, reminds me very strongly of two paintings, both are in museums – Gustave Courbet’s A Burial At Ornans (1849–50) and Pieter Bruegel’s Peasant and the Nest Robber (1568). In both these paintings, the hole sheers off the surface. It places the viewer into a strangely visceral spatial relationship where we become conscious of uprightness, and inevitability, of disintegration. In a funny sort of way ‘it is always going on’ by which I mean unfinished – a perpetual exchange between – it, artist, audience – hands and bodies.

The other point I want to make was how people touch things, sculptures, monuments, and how their touching changes the work…

JF: Touch is such an intimate, private act that stands in stark contrast to the exposed, very public nature of so many sculptures and monuments. I think we very quickly learn how to drown out the noise and potential interference of public spaces we inhabit in order to create a protective atmosphere of our own in which we can express unsaid and unsayable things. This is most evident, of course, in religious settings and the ways that worshipers touch the feet of saints while praying, and in doing so, create a golden, worn patina that speaks of centuries of prayer and attention.

It’s not often that acts of such intimacy become so visible in non-religious settings, but I do love the example offered by Oscar Wilde’s tomb, made by the sculptor Jacob Epstein in 1912. It received so much love in the form of lipstick-covered kisses from adoring fans that the sandstone began to erode and a glass barrier had to be installed to protect it, which of course, is now also covered in kisses. Destruction through love! I often wonder at what point people would stop kissing the glass; how many barriers is too many barriers to express your love?

This leads me on to consider the subject of failure. If a work is destroyed, it is often considered to have failed in some way. But I like the idea that destruction, whatever form it takes, is a kind of gathering action where we are introduced to something potentially more expansive that forges a powerful relation to a particular era or context.

JM: To pick up briefly on erosion and kisses, do you remember when Cornelia Parker wrapped string thread around Rodin’s The Kiss (1901–4), retitling it The Distance (A Kiss With String Attached) at Tate Britain in 2003 and someone cut the threads… basically destroying her work and restoring the Rodin? I think destruction-restitution is interesting in itself – and of course, the question of who has ‘the right’ to intervene with works in a public gallery’s publicly owned works. It is a thorny question – I don’t imagine Tate would appreciate Rodin himself changing work they had acquired – and there are plenty of examples of this kind of revision. The idea of completion is very complicated. And in ways, concepts like Rodin’s kiss, Brancusi’s kiss, Duchamp et al are returns to totemic / or iconic manifestations, long before any kind of commodification of art, culture… I think the desecration element in desecrations’ self-justification is deep-rooted repetition of the sacred and profane dichotomies…

Another example is the number of public sculptures – particularly bronze sculptures – in cities the world over that have certain body parts that have been touched and rubbed so many times that the patina has worn off, revealing the bronze beneath. Generally, but not always, breasts and genitalia. What is this – a desire to touch and communicate, or something more leery? Or both and neither…

If there was no possibility of failure, ie the work succeeds due to a preordained pattern, then what would be the point of risking its impossible resolution urges? Its possible failure is for me what keeps it alive – the doubting of being ‘in-between’ when a decision hovers and we simply don’t know but we have to take a plunge. For this, I hold Bas Jan Ader in high esteem, the openness of Yoko Ono’s performative writing… Bruegel’s representation of the fall of Icarus, and Auden’s lines on this –

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

JF: And this is exactly as it should be. To comprehend, accept, or mull over every failure is an overwhelming, impossible task. One person’s failure is necessarily another person’s distant splash. The idea of failure is subjective – who decides that something has failed and on what grounds? I received an email a few months ago from a curator telling me about a publicly sited artwork that she had worked on that had been destroyed in some way. Whilst those around her perceived the attack to be an act of vandalism which pointed to the failure of the artwork or the commissioning organisation, or the context as a whole, both she and the artist took the destruction as a positive engagement and wanted to explore ways of preserving it, in order for it to become part of the future narrative of the work. I’m interested in this opening up of the possibilities for public art; to put fear centre stage and embrace the unknown.

Can we round up our discussion with a bit of reflection on the archive? You’ve spent a large part of your career thinking through the various ways that archives are constructed, used and talked about. For me, an archive is a fantastically flawed, brilliantly vital repository of ideas, stories, and works of art, which holds within it limitless possibilities for interpretation, reinterpretation and re-situation. As Ines Schaber says, ‘the archive is not only a place of storage but also a place of production.’1

The impossible nature of an archive is also a reflection on how we are constantly stumped by the limitations of time – the archive is never complete and can only be viewed from the vantage point of an impossibly fleeting present moment and a context-specific present. I attended a talk recently in which the writer Jordy Rosenberg spoke about archives as dream states or portals (‘There’s so much falling awake and waking up in relation to archives’.)2 I’d like to mess with fact and fiction in the Archive of Destruction, play with the lack of documentation about destroyed artworks and shore up the ‘anti-fetishisation-of-the-archive’ movement by messing around with what might or might not have happened, and enjoying the potential for misleading my audience. This may be a reaction to my Art History study years, in which artist’s careers, movements, and slide libraries were presented as a series of static, linear, hierarchical entities.

A friend recently reminded me that when Apollo 13 went missing for three days in 1970 after an oxygen tank blew up on board the spaceship, Nixon’s advisors wrote a pre-emptive statement lamenting the death of the astronauts. When the astronauts made it home safely, the filmed statement was quietly shelved. I love the idea that this piece of documentary evidence concerning an act of destruction that never took place, creates an alternative history used to mislead generations to come, and potentially create alternative futures.

What is it that interests you about archives and the Archive of Destruction?

JM: Ok, what you said about the oxygen tank on Apollo 13 and Nixon’s political decision to historise this event, in effect faking documentation and creating an ‘alternative’, different – history – as a potential reading of what happened empowers doubt, scepticism perhaps as much as curiosity. I’d say this attitude is key to how I engage with archives. It reveals how an actual misreading, (which in this case was suppressed) leads to new reading of events – like science fiction – that might happen, or never happen. It identifies something precisely which chimes well with what I’ve been thinking about – that is, utilising the archive as a medium for the production of work, as a pattern that enables an archaeology of the future.

I don’t know that I could say I ‘like’ archives. Sometimes I feel the urge to light a fire under them… and for years, literally, I have had an empathetic ideological chord struck by the events of the Foksal gallery, Warsaw in 1967 when, on a day of happenings on the Baltic coast of Poland, they sunk the gallery archive in a chest – apparently! The photo recording the event shows the small rowing boat with two people on it and a chest addressed to the Warsaw Gallery. The press release refers to the intention to sink all the important documentation included in the gallery’s archive – press releases, correspondence, plans, ideas, photographs etc. Apparently a provocative discussion method they employed amongst themselves (as cooperative directors) was to put a bundle of papers into a kind of spinning wheel – to disrupt any previous order – and ‘dip’ into this mixture, taking the leads from the random juxtapositions. I included material from the ‘gallery archive’ distributed by mail to the UK – including from Jasia Reichardt’s archive, David Gothard’s archive and Richard Demarco’s archive (and a few others) in an exhibition entitled ‘Kantor was Here’ held at the SVA, Norwich in 2009. The exhibition traced presence of Polish artist Tadeusz Kantor and Cricot 2 – the group of artists with whom he collaborated – in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s.

Destruction, in theory, is also intrinsic to risk, and draws on the possibilities of doubt, which is what drives me, doubt… failure, measures to quantify and as well as unhinge monolithically established readings that don’t take account of the maybes, and the unspoken, the forgotten and the overlooked – as well as what and where the anecdotes might point towards.

Archives are to be ‘risked’ – we have to take risks in how we interpret them. This places me at theoretical loggerheads with the science and methodologies of the archivist. And of course, it is contradictory to the keeper’s role, which I obviously embrace on other occasions – although always from the (an) outsider’s position – I am not a trained archivist, I am ‘interested’ in the possibilities that archives offer us.