Artist Marysia Lewandowska makes the case for acts of destruction to be embedded within public discourse, archives, and collective memory – and for these modes of knowledge-production to be openly accessible, exploratory, and disruptive.

Imagine getting to know a city not by walking its streets but by identifying its cultural DNA through the work of artists, writers, and critics whose contributions are forever present in the collective memory. While many traces are no longer evident in the urban fabric, their powerful presence is recorded and made available through publications, archives, and publicly accessible documents which allow for the social imaginary to expand.

It is through publishing in its widest sense that multiple publics come into being. All ideas depend upon dialogue, ideas exchange and documentation of some sort, which ensures their longevity, relevance or extinction. Artists bear particular responsibility for the dissemination of practices marked by openness often found in grass-roots movements and friendships. It is in this spirit that the Archive of Destruction, by assembling a contested realm of artistic practices which often defy commodification and constitute a public history, is likely to become a catalyst for future creative work. What is presented here contributes to a dynamic that arises from engagement with the archive as a node in the supportive networks of commonly produced, commonly distributed, and commonly shared ideas. It is not only the outcome of creative work, which could be material or immaterial, but the form of social relations which must occupy discussions regarding preservation, protection and attribution of the ways in which artists, thinkers and cultural agents work. All of this will no doubt help us move on from thinking of archives as stores of documents, and get closer to an idea of a desiring archive, a reservoir of affective materials and a source of nourishment, full of contributions coalescing around a collective effort based on generosity.

Some years ago in a talk given in London, the artist Anri Sala referred to his early work Intervista (1999), which he made after discovering two fragments of a film that had no sound. The excepts were made up of interviews with his mother who was an activist in the Albanian Youth Communist Union. The work itself is a valuable expression of the artist’s search for his mother’s ‘lost words’, combining the intrigue of a detective tale with the intimacy of a home video. Intervista makes a powerful case for the discovery of alternative narratives that supersede previous prescriptive readings (in this case, communist propaganda).This serves as an example of how an artist’s intervention, through affect generated by the material loss, is capable of interrupting the existing flow of historical claim.

Unlike earlier social and political periods, we are experiencing our present as one that can be instantly archived through new forms of digital and social media. This imperative turns life into a constantly replicating set of procedures that involve a continual process of selection, curation, definition and contention. In a culture dominated by commercial concerns and capital growth, we assume that the acquisition of cultural value often known as ‘heritage’ involves the introduction of property rights over images, sounds and objects. Network culture and digital production have led to a crisis of value, where knowledge is expropriated under the regime of capital. Under these conditions, can the imaginary character of property still be rescued and re-inscribed? Hannah Arendt in her description of the rise of consumerism seen through the lens of private and public distinction and their corresponding activities, contrasts labour and action. Action expresses our highest potential through which we are recognised by others and are able to disclose our uniqueness and willingness to participate in something larger than ourselves. With the loss of action and the increasingly privatised public sphere, freedom is reduced to routinised ‘behaviour’; difference and plurality to conformism and uniformity; speech and self-disclosure to relentless production and consumption. Instead of experiencing the freedom associated with action and speech in the public realm, we are reduced to mere adjuncts in the cycle of production and consumption. It is the end of action and the end of speech.1

What the Archive of Destruction as a project attempts to do is recall the energy residing in the past – not the past as such. Certain events and modes of operation have been suspended in time but they never die, their particles continue to nourish the culture which has rejected or destroyed them. When actions disappear from view, they gain a different kind of power, they are absorbed or buried in a collective memory, sometimes triggering a need for expression. When little evidence is available, we begin to fill in the gaps, constructing the armature of fiction as an extension of hope. Artists and activists are often those daring self-appointed representatives of the collective unconscious, spinning yarns, playfully reckoning with the past. They are prepared to take calculated risks for unspecified reasons, by default opening up the circuits of truth or half-truths, upholding justice for others. It is often in the act of destruction, intended as well as accidental, that material fragility summons our attention, releasing a different kind of force, one in which resilience emerges through the process of questioning and public conversation. Documenting dissent and creating an understanding around the circumstances and context of particular events is never institutionally or emotionally straight forward. Unmuting and listening to an unleashed social anger requires the engagement of multiple actors capable of collectively identifying cracks in the narrative.

Everything will be taken away. Adrian Piper, 2003

Deploying archival tactics by stating political stakes more precisely may help create a greater ethical commonwealth where issues of origin, cultural diversity, and colonial expropriation are articulated without prejudice or preconceived ideas. Idiosyncratic methods of recording and documenting present a legitimate challenge to the Western canon of representation and its entrenched system of knowledge hierarchy and acquisition. Our individual cultural habits are hardly able to represent immaterial, unfixed, affective and metabolic processes that extend beyond rational and calculated outcomes. Often the inexplicable power of the commons and spiritual kinship expressed in joining efforts to speak truth to power erupt through a single event, with the art object as its catalyst. Rage or protest doesn’t require authorisation but they do need a clear signal. That signal – often an image or art object – carries the real possibility of political mobilisation. The perceived safety of institutionally-sanctioned art practices, however uncomfortable or critical, uphold only a narrow concept of privilege and established value systems. In contrast, unofficial documents, often found in personal archives, strengthen the capacity to voice dissent with their unpredictable impact leaking into public discourse.

Partially Buried Woodshed (1970) by Robert Smithson and its conceptual premise of slow release into the social imaginary, is analogous to processes embedded within the archive. The idea of seclusion, revelation and release are central to both. Smithson’s gesture points to several instabilities that align with the idea of the archive as a site of commemoration, legal enclosure and political vulnerability. Nothing can protect a memory from suppression, erasure or neglect. In Smithson’s case, the work performs its own loss through a process of decomposition and exchange of energy. Dissolution of material fabric has been accelerated by the natural agency of gravity, fungi and enzymes. Smithson’s decision to foreground decay played a seminal role in activating the artist’s relationship to archiving. A reverse of preservation is fermentation, a word often used metaphorically, to explain the beginning of both life and political change. Allowing natural forces to take their course involved a process of letting go, relinquishing control to be reclaimed by the earth. In this play of entropy realpolitik events intervened, adding stress to the already fragile construction. The shooting of students at Kent State University on May 4th 1970 found a perfect screen upon which to project this tragic memory. Reclamation of Partially Buried Woodshed by natural forces was interrupted and hijacked. Its disappearance from view re-appeared as the ghost of a deeply disturbing event, sharing not just the site of the university campus where the artwork was originally made, but a larger context of contestation. Smithson’s anti-monument has entered public consciousness, implicating the art work by symbolically linking it with American history and the Vietnam War. Looking back is always retroactively charged. The past, however painful, must be acknowledged, and the archive may be harnessed as a placeholder for registering such pain.

Everything is near and unforgotten. Paul Celan 1944

Once an artwork occupies public space, its capacity for generating public discourse begins. This is abundantly clear with the art of Michael Asher2 whose practice relentlessly exposed the rigid conformity of the art world and its institutions. His singular approach to the importance of context foregrounded the contingencies of the undocumented and unspoken. Close examination of the gestures of re-location and re-assembly allowed for shifts in understanding the mechanisms of power inherent in exhibition-making and modes of display. By challenging existing norms and habits of thinking and looking, his precise activation of context led to the undoing of memory and the creation of new memories. A public work, while offering itself to everybody, is often employed as part of a transactional culture of spectacle. However, it is able to retain a capacity to unmute public consciousness through a powerful act of self-authorisation.

Everything in the world belongs to somebody. Christo 1968

Archives mimic a wider cultural shift in which conservation is now aligned with monetisation through expropriation and prohibitive licensing rules. Access to materials which have largely been donated by individuals with the aim of benefiting us all are now frequently withheld. Ownership is a battleground and legal tools are designed to keep much of collectively produced knowledge out of reach. Copyright’s destructive powers are often motivated by a drive to maximise revenue and exercise control over a person’s or artwork’s image as well as reputation. This has resulted in a tussle between more stringent copyright legislation, and increased awareness around fair use and alternative ways of community-based licensing. Fair use jurisprudence allows for greater discretion in granting access to copyrighted materials, particularly if the new use has a different purpose to the original. Archives can only benefit from adopting such procedures and granting requests for use and re-use of these ‘locked away’ materials.

One of the most explicit examples of copyright control is the closely guarded way in which Martin Luther King’s estate retains a tight hold on King’s legacy. When his speeches were delivered in the 1960s, copyright subsisted in common law and, as later argued in the courts, while he was performing his famous 1963 address live, King stated that they should remain in the public domain. ‘A performance, no matter how broad the audience, is not a publication; to hold otherwise would be to upset a long line of precedent. This conclusion is not altered by the fact that the speech was broadcast live to a broad radio and television audience and was the subject of extensive contemporaneous news coverage. We follow the above cited case law indicating that release to the news media for contemporary coverage of a newsworthy event is only a limited publication.’3 Once legal institutions privilege private property over community interest, our ability to access facts and artefacts is curtailed.

Might the archive be seen as a site of destruction in reverse – collecting and laying bare the process of social sedimentation while identifying and undoing its knots? The Archive of Destruction foregrounds the political importance of rupture. It introduces contingencies of knowledge production and exposes forces which contribute to the process of commemoration. Out of the hiatus that appears in the space between two states – no longer and not yet – it offers the benefit of the doubt to the efficacy of public discontent. What has not been settled through debate or negotiation finds expression in a ritual of destruction. Most of the conceptual projects included in the Archive of Destruction cease to exist when their work is done; documentation therefore acquires special significance. The archive creates an opportunity to accept destruction not as a threat but as a consequence of dissent that plays a part in the emancipatory potential of society. It allows a space for reconstruction and, more importantly, remediation in which original events can be situated and considered from a perspective of accumulated knowledge. Gaining knowledge as a form of empowerment encourages re-evaluation of dominant narratives and acts as a salutary reminder that knowledge is separate from ownership.

Everything is just fine, no problems at all. Popular French song.

While ease of self-archiving has increased with digital technologies, access has suffered set-backs from gatekeepers. In 2019, Getty Images sold their stock of three hundred and fifty million assets to Microsoft, and in the process handed over licensing rights of every image, video and voice held in their catalogue. In the year 2000 Mark Getty, the grandson of J.Paul Getty, famously proclaimed Intellectual Property to be the oil of the 21st century.4

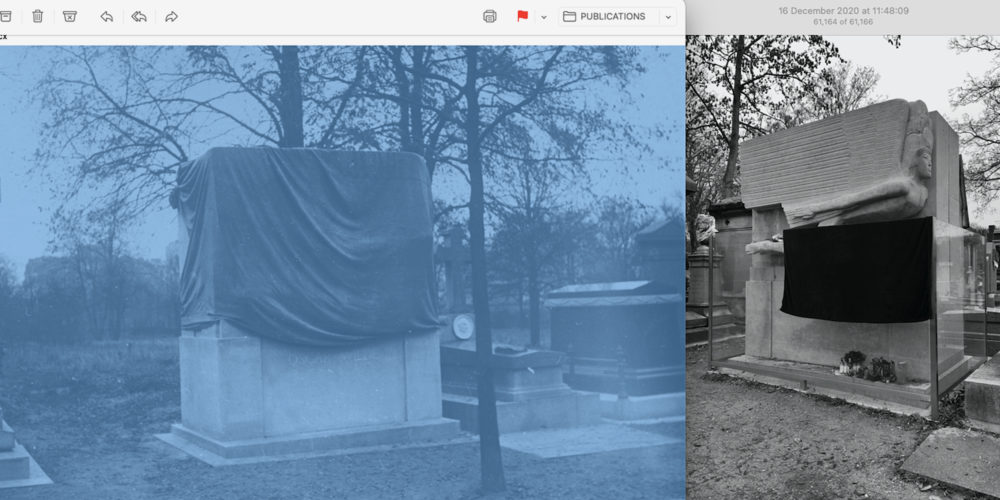

One of those photographs is an image by Roger Viollet showing Oscar Wilde’s tomb shrouded in black canvas. Jacob Epstein’s explicit depiction of male genitalia was deemed to be too offensive for public display and was duly covered for two years from 1912 to 1914. Getty Images corporation holds rights to the thousands of photographs which comprise the Roger Viollet Collection. Refusing to pay the reproduction rights of Viollet’s image to illustrate this text, I asked Paris-based artist Camille Benarab-Lopez to respond to the original photograph. She staged and documented a performance in which a woman unsuccessfully attempts to cover the tomb. By actively engaging the memory of the image, the artist grants us access to what can be considered the ‘anti-event’. The fate of Epstein’s sculpture, visually unavailable for two years, is now shared by its photographic record, which has been deposited and buried in the vast digital vaults of Microsoft. This fleeting new iteration of the story of Wilde’s tomb is a reflection on the ways in which current conditions of ownership effect our ability to produce an alternative public memory.

Archives, like collections, are built with the property of multiple authors and previous owners. But unlike the collection, an archive designates a discursive terrain and not a particular narrative. And therefore in the archive interpretations are invited and not already determined. There is no imperative, within the logic of the archive, to display or interpret its holdings. Everything can be interrupted.

With thanks to Camille Benarab-Lopez for her performance piece and photographs of Oscar Wilde’s tomb.