Lots of things happened in America in 1901. The stock market crashed for the first time; President William McKinley was shot, Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in; the summer saw the worst heatwave in US history; The Great Fire in Jacksonville, Florida destroyed 2,300 buildings leaving 10,000 people homeless. But the most significant event of that year took place on 10 January when oil was discovered in Spindletop, Texas, and the course of US history changed forever.

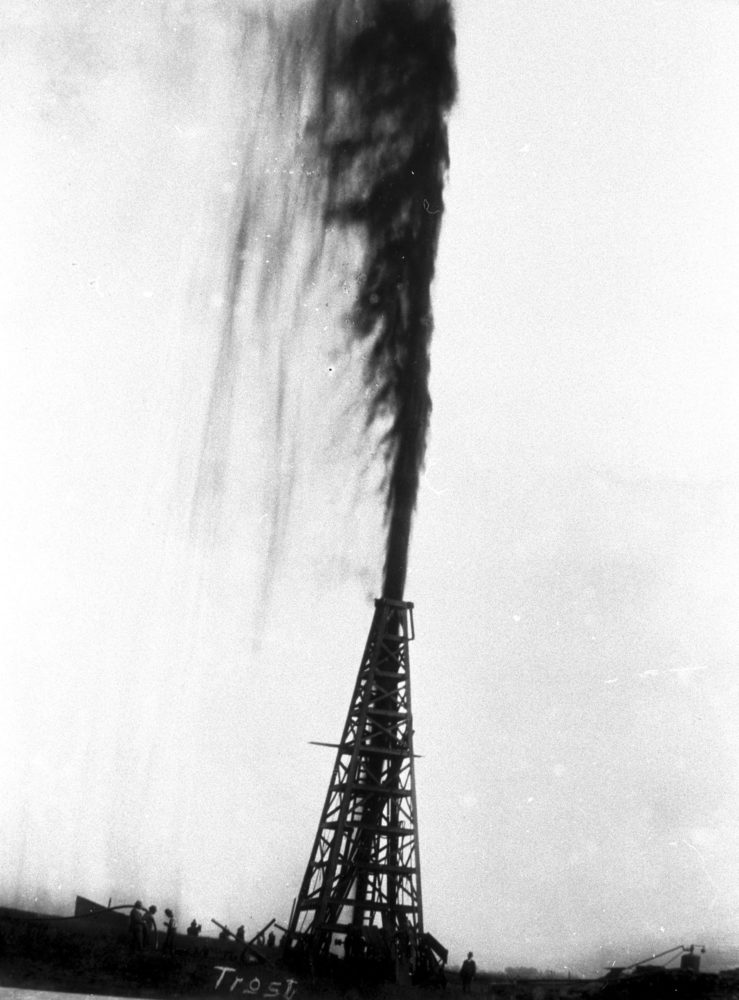

Prospectors were following the hunch of a one-armed geologist when they dug a 300 metre deep exploratory well which hit a reservoir so vast that its puncture caused a small earthquake. This 45 metre geyser exceeded the combined production of every other well in the USA on that day and was the largest oil strike the world had ever seen. It was ‘the starting gun for a boom that would transform Western society and, ultimately, the Earth’s entire ecosystem.’1

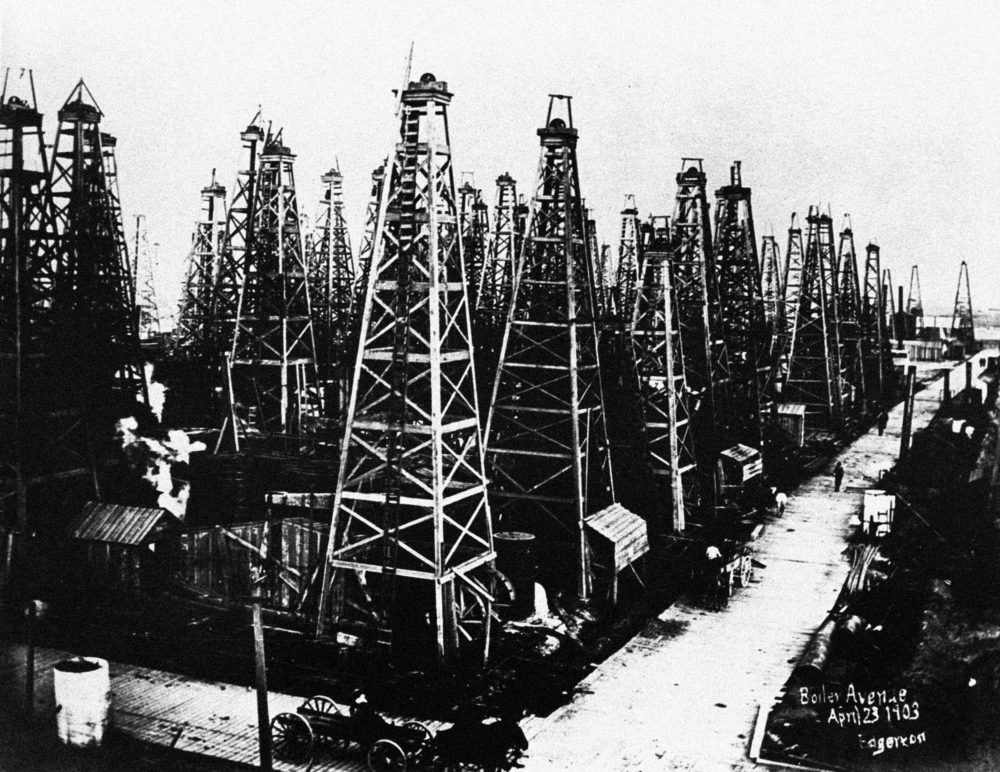

Two years later, that single derrick situated in an otherwise deserted landscape was joined by hundreds more, all operated by newly constructed, soon to be global, companies including Texaco, ExxonMobil and Gulf Oil.

Irish artist John Gerrard used the two contrasting photographs that document this radical expansion of oil drilling capability as the conceptual backbone of Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) (2017). Commissioned by UK TV station Channel 4 to mark Earth Day, this digital work depicts an exquisitely detailed, real-time simulation of the now barren and exhausted site of that discovery in Spindletop. Smoke spills out from seven nozzles located at the top of a pole, echoing the form of a flag billowing in the wind. When the sun goes down in Texas, the flag is shrouded in darkness. This live simulation is constructed from thousands of photographs of the site which are then translated into code. Refusing the logic of documentary photography or pre-recorded film, each one of the fifty images that are produced every second, is discarded, producing an effect that comes close to echoing real time.

When this invisible sculpture was live-streamed on YouTube for a month, viewers found elaborate ways of incorporating sections of the stream into their own films, thereby creating a further palimpsest of layered imagery. When it was broadcast on Channel 4 twice an hour for 24 hours, the process followed the day/night pattern embedded within the television schedule. No explanatory text or voice-over was supplied; home decorating shows were spliced directly into the flag-billowing image, creating a jarring provocation to viewers. Representatives at Channel 4 liaised with OfCom, the UK’s communications regulator, who were aware that the image could be considered by viewers to be a threatening symbol, potentially linked to the black flag of the caliphate. Twitter was set alight; hashtag debate ensued over the potential meaning and author of the intrusion.

Gerrard’s work is an attempt to make our consumption of, and reliance on, oil visible. In his words, it is a ‘mourning or grieving flag’ which insists on recognition of the fact that our way of life is no longer tenable:

One of the greatest legacies of the 20th century is not just population explosion or better living standards but vastly raised carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. A new flag attempts to give this invisible gas, this international risk, an image, a way to represent itself. I like to think of it as a flag for a new kind of world order.2His tone becomes more urgent in a lecture he gave in Madrid in 2019 when he stated that an important ambition for the work was that we ‘…acknowledge that climate change denial is a form of extreme violence towards the most vulnerable people on earth’.3

Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) has become part of an on-going narrative about the climate emergency and the destruction we are reaping upon the earth. It has been shown on frameless LED walls situated in public sites and courtyards at Somerset House in London (2017), the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid (2019), and Coachella Valley as part of the Desert X exhibition in California (2019), its ghostly, simulated form gaining traction and a renewed sense of urgency in each location.