Since 2016, Austrian artist Katharina Cibulka has been installing large-scale fabric text works on the façades of buildings across the world. Collectively called SOLANGE (German for ‘as long as’), they form a critique of gender-specific social inequalities and power structures in contemporary society, calling for the empowerment and equal treatment of women.

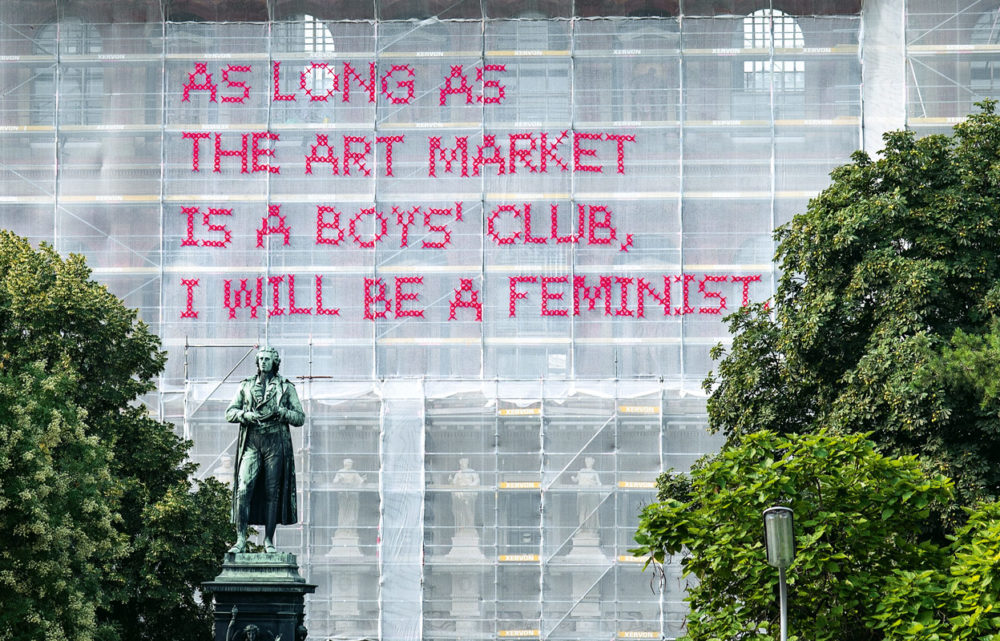

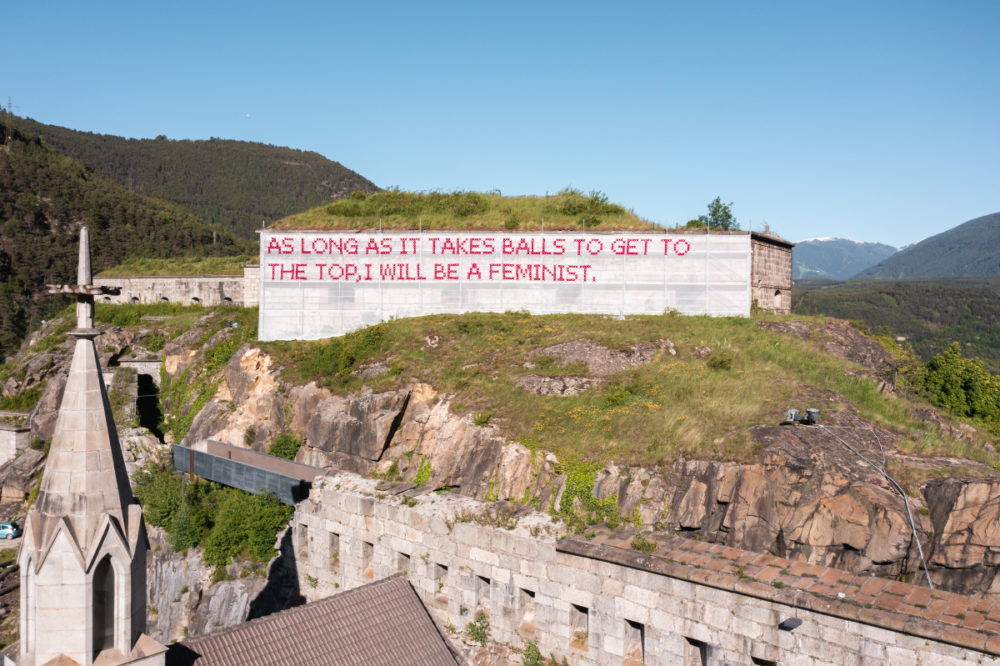

Cibulka’s selected sites are heavy with meaning, either through their status as long-standing august institutions laden with patriarchal baggage, or as construction sites – places populated primarily by men. In the gendered language of pink cross-stitch applied to construction netting, the words ‘As long as the art market is a boys’ club, I will be a feminist’ were installed across the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna; on the Cathedral of St James in Innsbruck: ‘As long as god wears a beard, I will be a feminist’; on a fortress in South Tyrol: ‘As long as it takes balls to get to the top, I will be a feminist’; and on a building under construction in Landeck: ‘As long as power entices men to misuse women, I will be a feminist’. Public space, in Cibulka’s eyes, is political space – a non-neutral place in which societal power-structures are displayed, enacted, and challenged.

For each work, the artist interviews local people, posing the question: “How long will you be a feminist?”. Responses are collated and a single sentence is embroidered onto pieces of tulle in pink, metre-high letters. Reflecting on the agency embedded within the work, Cibulka has said that “It is a kind of constructive provocation that withholds blame or judgement.”1

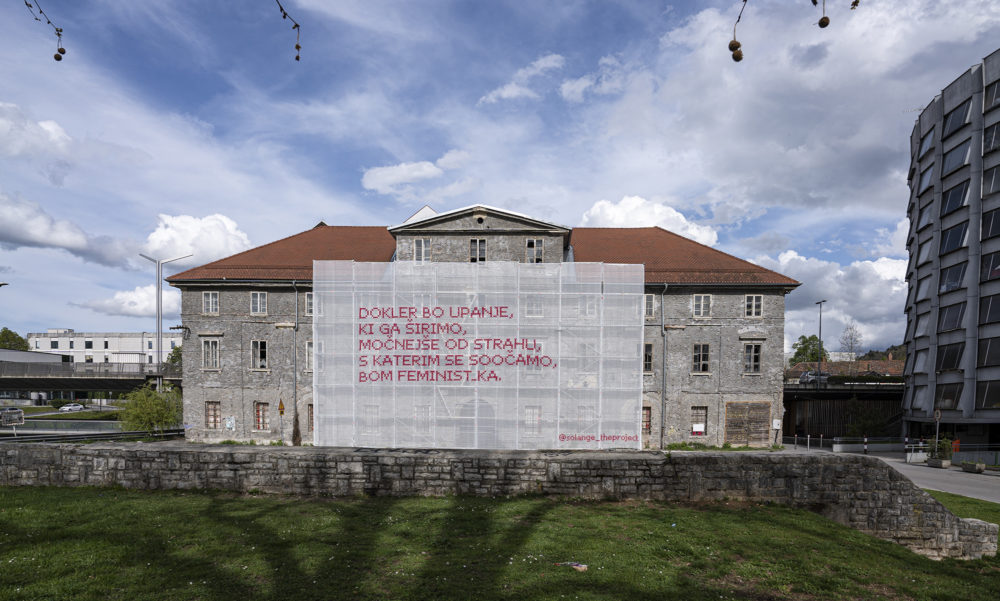

On 30 April 2021, the latest version of SOLANGE was installed on the façade of Cukrarna Palace in Ljubljana, Slovenia. The words: ‘As long as the hope we spread is stronger than the fear we face, I will be a feminist’ were emblazoned across the building. The installation was part of an off-site programme for the exhibition When Gesture Becomes Event, which opened on the same day at the City Art Gallery Ljubljana. A few days later, on the 3 May, the work was destroyed by unknown perpetrators, with only the words ‘upanje’ (hope), ‘strahu’ (fear), and ‘se soocamo’ (we face) remaining intact.

In a statement, gallery staff recognised the hostile context in which the work was viewed:

The event dismayed and saddened both us and the artist. We are afraid that the action testifies to a great degree of intolerance in our society, leaves a bitter aftertaste in relation to new development projects in the capital, and shows a hostile attitude to socially critical art. People who cannot find words for their discomfort, their frustration, their anger resort to violence – in this case towards a public work of art.2In a public statement that was reported in newspapers across Slovenia, Cibulka spoke of the enduring power of art to unite and empower people – even if a work is destroyed:

It saddens us that our sentence, in all its poetry, was apparently not understood by some. A work of art can be torn apart, but not our belief in its power to unite and encourage people. We firmly believe that the challenges we face as feminists can only be solved when we work together. 3Drawing attention to the particularly febrile atmosphere of 2021 bought about by the global pandemic, Cibulka spoke about her work holding particular resonance at a time when “we are afraid of illness, job losses, the destruction of nature, and the need to maintain hope”.4

Blaž Peršin, the Director of the Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana, echoed this view and proposed that the damaged work remain on site:

The vandalism we witnessed is a reflection of the times we’re living in, which is why the City Art Gallery Ljubljana will suggest to the artist that her damaged work remain on the façade of the Cukrarna Palace as a mirror to all of us, reminding us where we’re heading as a society and how much fear is still present among us.5Exhibition co-curator Alenka Gregorič added that although the event shocked and saddened staff at the City Art Gallery Ljubljana, they were heartened by the many responses and words of support they received. Whilst condemning the destruction of the work, they hoped that the action would stimulate public debate about equality and solidarity.