That’s Hew Locke speaking in 2017 about Restoration, his series of photographs of contentious, imperialist statues located in Bristol, UK, including Edward Colston and King Edward VII. They are an attempt, said the Guyana born, London raised artist, to “reveal a hidden story and to get ownership over my landscape”.2 He mounted the 121 × 182 × 15 cm photographs onto aluminium, drilled holes into the prints, and adorned each statue with a suffocating array of seemingly celebratory, jewel-like decorations. On closer inspection, these items include small replicas of skulls, skeletons and slave ships. Locke called this series a kind of ‘mindful vandalism’.

The statue of Edward Colston (1636–1721) is bedecked with the trappings of his wealth that reference his exploitation of Africans over decades, including cowrie shells – a commonly used slave-trade currency in West Africa. A hugely divisive figure in Bristol, Colston was a philanthropist whose name is given to over twenty civic institutions, street names, traditions, and pubs throughout the city; many residents consider him to be the founding father of Bristol. But this wealth was made from the industrial-scale slave trade that he brought to the city, which involved the transportation of tens of thousands of shackled slaves from West Africa to the Americas.

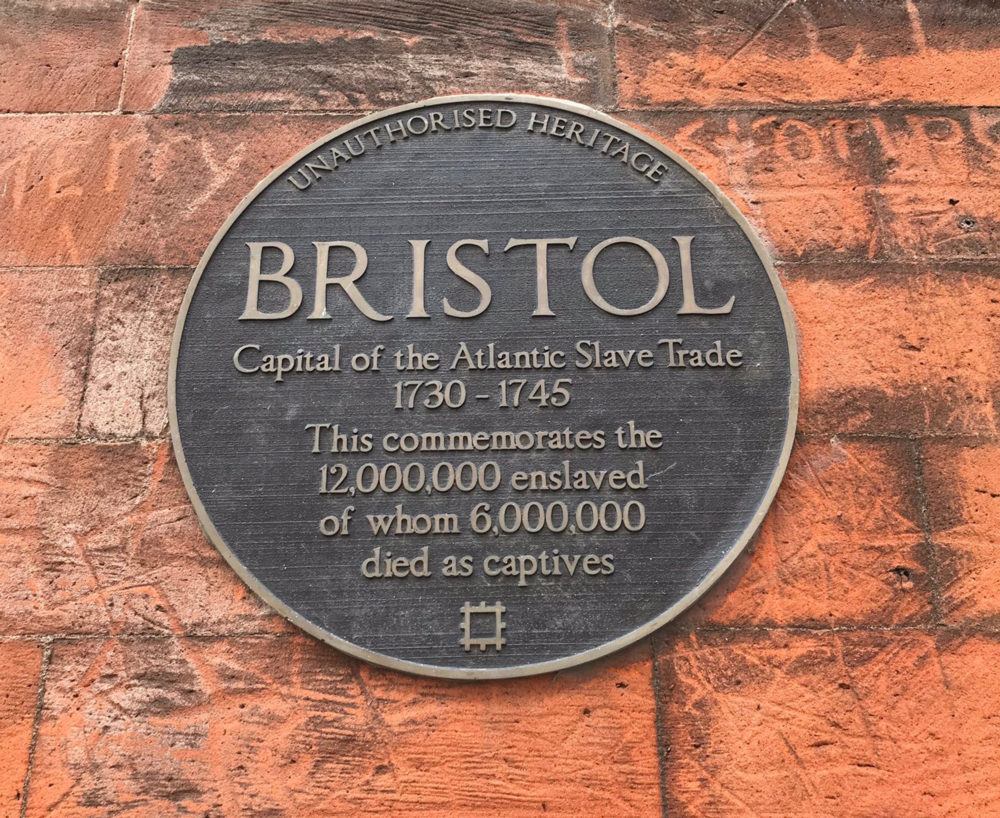

A long-running campaign to remove the Colston statue was instigated by members of Bristol’s Black community, historians and activists. When their activities came to nothing, they installed an ‘unauthorised heritage plaque’ next to the official one:

The act prompted a protracted round of discussions concerning the re-wording of the official plaque which also came to a stalemate.

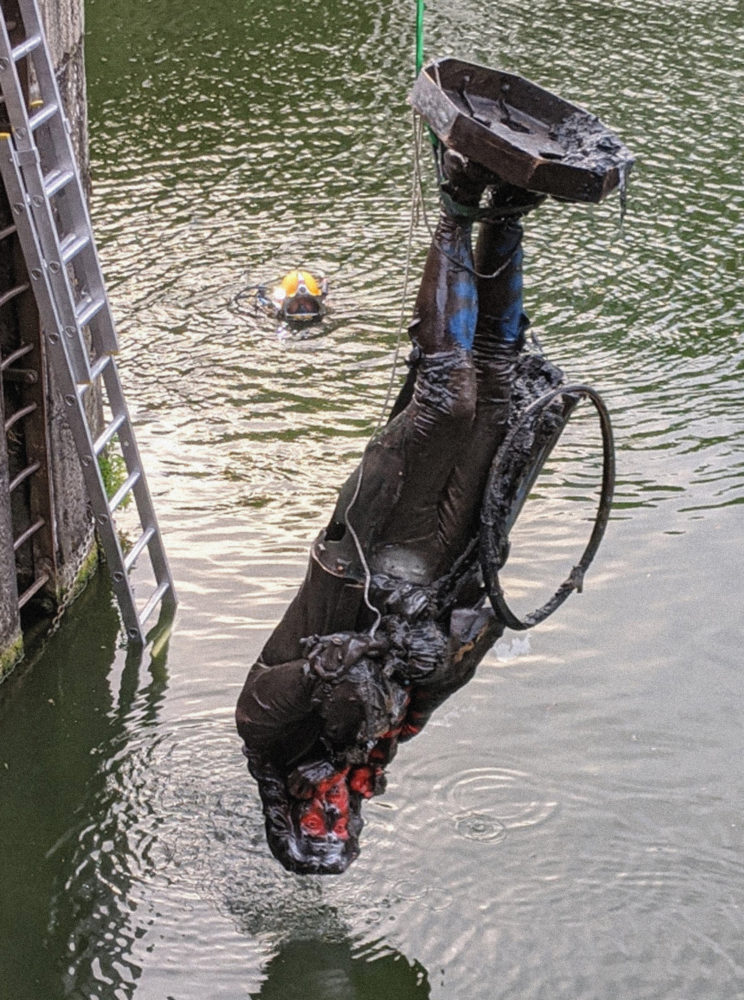

When Locke told an interviewer that he would love to have redecorated Colston’s statue for real, perhaps ‘wearing a balaclava and doing it in the middle of the night’, he had no idea that three years later, the statue would be torn down, dragged ceremonially through the streets, and thrown into the murky depths of the harbour by Black Lives Matter protestors in the midst of a global pandemic.3 The act, carried out on 7 June 2020 as a response to the brutal murder of African American George Floyd by Minneapolis police, became the rallying cry of the UK protests, sparking multiple statue-toppling acts across the world, and heralding the start of a nation-wide debate about police brutality, systemic racial injustice, colonial legacies, and white privilege.

The Colston statue was dredged from the harbour by Bristol authorities four days after it was thrown in. Locke called it a huge anti-climax:

I knew that he would have to come back up again – that’s the way things go – but leave him down for a little while…please!4Conservationists began working in a ‘secret location’, ensuring that the red paint and graffiti that was daubed on Colston’s head and body during the protests were conserved:

…that’s actually the most fragile part of the sculpture. It has become part of the story of the object, of the statue, so our job is to try and retain that as much as possible, while stabilising the statue for the long term.5Discussions are underway concerning the most effective way of disposing of, or re-installing, the Colston statue. Like Locke, some wanted to leave it languishing at the bottom of the harbour where Colston’s slave ships docked; others proposed to melt it down and reuse the steel to make another, more fitting memorial or artwork. The most likely outcome is that it will find a home in a Bristol museum where its story will be contextualised and the idea of the museum as ‘an inherently apolitical space’ untethered by histories of Empire will be perpetuated.6

Openly racist statues across the world, including the Theodore Roosevelt statue outside the Natural History Museum in New York, and the many King Leopold II statutes located throughout Belgium, have either been removed in the aftermath of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests or are under consideration by authorities and institutions. Commentators, museum directors, historians, activists and artists have called for a radical rethinking of the way we view and commemorate history in our public realm.

Meanwhile, the evolving narrative of the Colston statue developed into a debate about white male privilege when internationally established artist Mark Quinn installed one of his own sculptures on the empty plinth vacated by Colston. Quinn installed A Surge of Power (Jen Reid) illegally over-night on 15 July 2020, using his considerable wealth to finance the undertaking. This 3D scanned resin statue showed Bristol-based, Black Lives Matter activist Jen Reid replicating the defiant stance she assumed during the BLM protests in previous weeks when she scaled the Colston plinth and raised one arm aloft in a Black Power salute.

A nation-wide furore ensued and two camps emerged, one broadly supportive of the work as an act of solidarity, the other decrying it as a dangerous act of colonialism that hijacked the BLM movement. Black artist Thomas J Price provided an excoriating critique: “For a white artist to capitalise on the experiences of Black pain, by putting themselves forward to replace the statutes of white slave owners seems like a clear example of a saviour complex and cannot be the precedent that is set for genuine allyship.”7 Another Black artist, Larry Achiampong, took to Instagram to vent his anger and frustration: “Sometimes the best thing that you can do when you’re part of the problem is to just stop”, a sentiment echoed by Bristol Mayor Marvin Rees (himself a descendent of enslaved Africans): “An empty plinth at this time is one of the best expressions of where we are.”8

There’s a complex layering of privileges and positions here, a situation starkly revealed by the fact that Marvin Rees received death threats and racial abuse from the far right group Britain First as well as BLM protestors as a result of his decision to remove Quinn’s work. In justifying his actions Rees said: “I didn’t take down the statue of a Black woman. I took down the intervention of a white, London-based artist using his financial clout to put his work on that plinth”.9 Many people, Black women in Bristol in particular, felt hugely empowered by the Jen Reid statue, and voiced their support on social media, staging re-enactments of the Black Power salute around Quinn’s work. Those ‘in the know’, working within the visual arts infrastructure, who were well versed in Quinn’s problematic appropriation of minority issues in past work, grappled with the difficult task of honouring this surge of empowerment while also critiquing the methodology of its making.

A Surge of Power (Jen Reid) was removed by Bristol City Council on 16 July, less than twenty four hours after it was installed. The council invoiced Quinn’s studio for the cost of de-installing the work.