It took Trevor Paglen ten years to realise his ambition to launch a sculpture into space. Working with a team of scientists from aerospace firm Global Western and staff at the Centre for Art + the Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art, Paglen’s project, called Orbital Reflector, was designed to encourage people around the world to ‘re-envision space as a place of possibility’. As with many of his wide-ranging, forensically researched projects, Paglen’s interest here lies in critiquing a political, social and technological system that has surreptitiously installed a tentacled, intricate web of surveillance and data collection networks across the world, in deserts, oceans, and even space. What if, he asks, instead of condoning the large number of nuclear missile targeting systems or mass surveillance devices that are launched into space every year, we start to consider that there are different, more creative, less invasive, ways of thinking about, or acting in, the world?

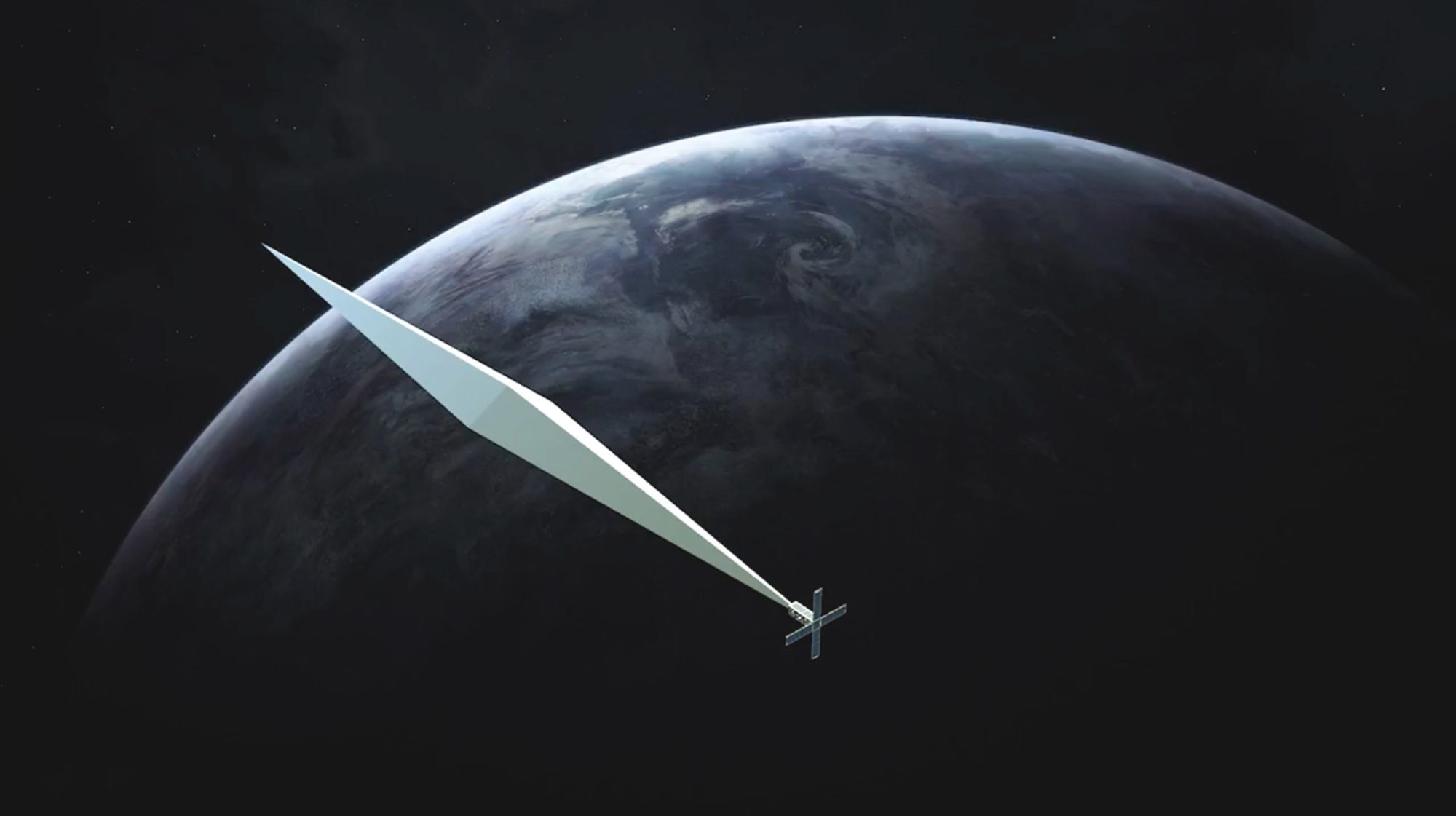

Paglen’s satellite was launched into space from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on 3 December 2018 along with 64 other satellites. The $1.5m budget was raised through a Kickstarter campaign and a myriad of applications to trusts, foundations and sponsors. The plan was for the satellite to be delivered 350 miles into the thermosphere – one of the layers of Earth’s atmosphere – before being inflated, away from the cluster of other satellites with which it had been launched. Partly inspired by the Russian painter Kazimir Malevich’s vision of a world orbited by artworks, called ‘Sputniks’, Paglen’s ambition for the sculpture was for it to reflect the sun back to Earth, from where it would appear as bright as a star in the Big Dipper. Trackable via a sky-watching app, the satellite’s life-span was estimated to be around three months, after which it would burn up in the atmosphere, drawing the project to a performative close.

Two unexpected things happened. One, the US Air Force was unable to identify Orbital Reflector from the other 63 satellites. And two, the Federal Communications Commission was ‘unavailable to move forward quickly due to the US government shutdown’.1

Lasting 35 days (22 December 2018 to 25 January 2019) this shutdown was the longest in US government history, and came about because President Donald Trump refused to agree the terms of a Congress bill to fund federal government operations for that fiscal year – his proposed US/Mexico border being the sticking point. The debacle caused wide-spread chaos, stock-market panic and financial hardship for many.

By the time the shutdown ended, the communication system on the satellite had failed, in effect destroying the work. Paglen’s team came to the conclusion that the small brick-sized box containing the balloon continues to orbit the earth, but because of its small (uninflated) size it will likely be a few years, rather than months, before the sculpture burns up in the atmosphere.

Some commentators were critical of this piece of ‘land art in the sky’, even before it took flight: Trevor Paglen Is About to Launch a Reflective Sculpture Into Outer Space, and Astronomers Are Really Pissed Off About It (Artnews)2 and Hey Artists, Stop Putting Shiny Crap Into Space (an astrophysicist quoted in a Gizmodo article).3 A group of astronomers were concerned that the satellite would cause light pollution which could interfere with astronomical observations, and others dismissed the project as an absurdly expensive, fruitless endeavour.

The project’s premature end required the construction of a hastily re-arranged narrative. A Nevada Museum of Art press release stated that the project had succeeded in its aim to create the conditions for people to ask ‘serious questions about who controls space: Does anyone own it? And who ultimately decides how it is used? The final chapter of Orbital Reflector brings these questions and issues to the forefront.’ Paglen communicated his thoughts in a Medium article: … I think what’s happened is a poignant illustration of who has the right to do what with our planet, which is fundamentally collective. He goes on to say that, ironically, Trump’s willingness to shut down the government … has killed a sculpture that’s supposed to be the antithesis of that. His final thoughts are a reflection on the more poetic aspect of the unexpected turn of events: I think of Orbital Reflector’s current state as being in a state of unknown possibility, like an unopened present circling through the night sky.4

The story of this lost sculpture involves a palimpsestuous layering of destructive acts: the destruction of the original intent; the delayed destruction of the artwork; and the ruinous fall-out of President Trump’s policies. It is a signifier of the times in which it was conceived and launched, and is made all the more poignant by its uncertain future.

Like digital art, Orbital Reflector extends the parameters of our understanding of what constitutes ‘public art’ but it also poses a more existential series of questions relating to the idea of witness (if we can’t see it or track it, how do we know it exists?), infinity, the sublime and hubris – pointing ultimately to humanity’s fragile relation to both itself and space.