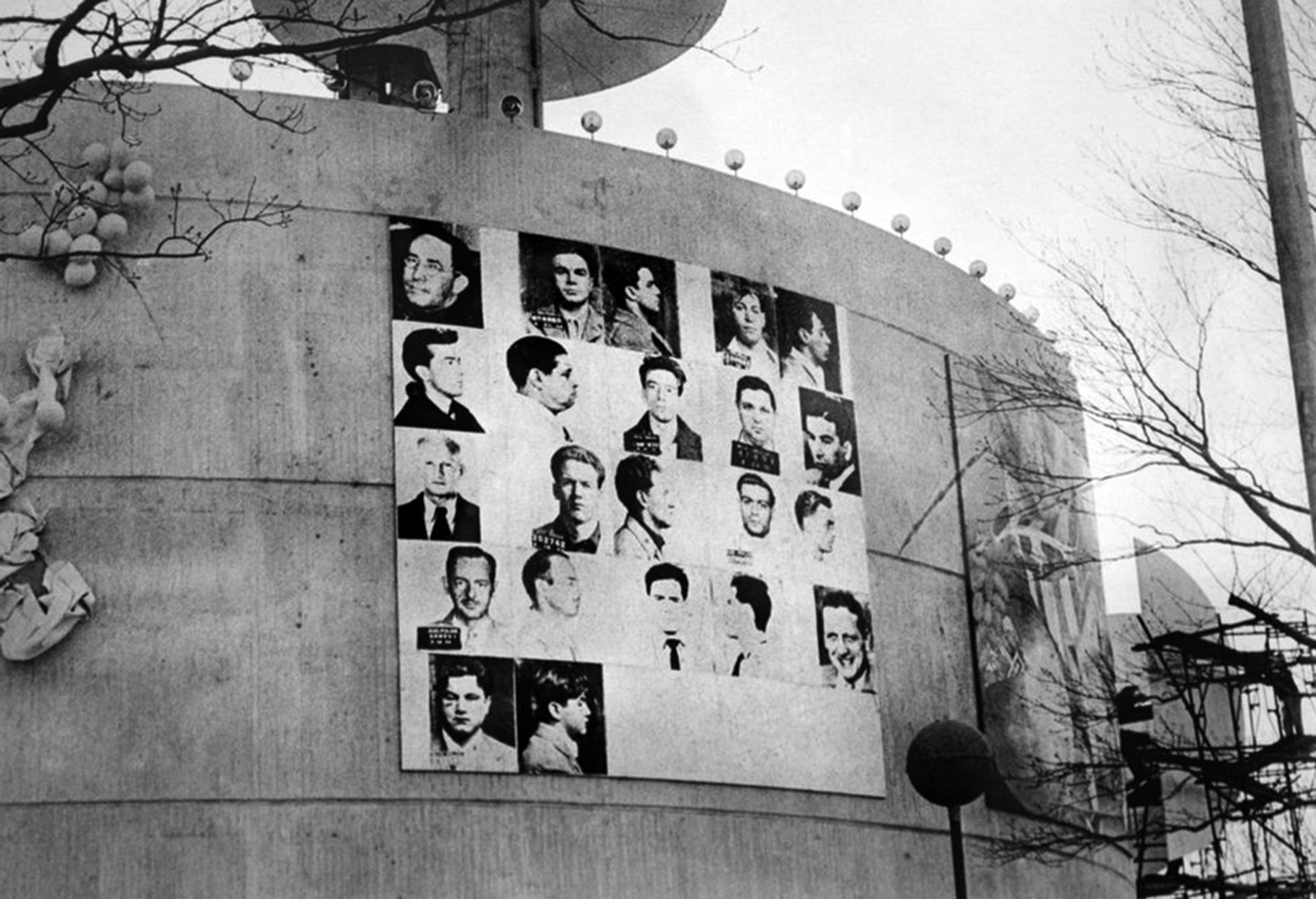

When Andy Warhol was invited to decorate the façade of the New York State pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1964 the expectation was that he would produce a celebratory work that would represent the best of America – Coke bottles or some such. Instead, the artist screen-printed the portraits of thirteen of the FBI’s most wanted men on a thirty-metre wide canvas that was draped over the Circarama, a circular cinema within the World Fair complex.

These portraits constituted vastly enlarged mugshots of mainly Italian-American gangsters, one of whom carried facial injuries commensurate with police brutality. Together, they make up a candid, disarming and even moving display of tenderness in the public realm. The pun on ‘most wanted’ men was considered by some to be an allusion to homosexual desire.

Warhol stated that he intended to depict ‘something to do with New York’ and that he took inspiration from Marcel Duchamp’s 1923 work Wanted, $2,000 Reward in which Duchamp put his own photograph in a wanted poster.

Two days after the work was installed on 15 April 1964, before the opening of the Fair, Warhol was ordered to remove it by a less than delighted city administration and an outraged Philip Johnson (architect of the pavilion). The work was obliterated with aluminium house paint (Warhol’s trademark colour “…silver is so nothing. It makes everything disappear.”)1 and when the Fair opened to the public, all that was visible was a large blank square.

Various stories circulated concerning the curtailed life-span of the commission. The Governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, was worried that the depiction of mostly men of Italian descent would be insulting to an important segment of his electorate. Other whispers that gained traction included the idea that Warhol himself was dissatisfied with the work, or the way it had been hung, or even the possibility of legal liability as one of the men depicted had been pardoned.

With his well-honed, dead-pan wit, Warhol suggested that he could replace the mural with twenty-five portraits of Robert Moses, president of the World’s Fair Corporation.

Later, in the summer of 1964, Warhol produced another set of the Most Wanted Men paintings with the screens he had used to make the mural. In his 1980 autobiography he wrote “In one way I was glad the mural was gone. Now I wouldn’t have to feel responsible if one of the criminals ever got turned in to the FBI because someone had recognised him from my pictures.”2