Between 14 and 15 January 1968, an earthquake with a magnitude of 6.1 destroyed the Sicilian towns of Gibellina, Salaparuta and Poggioreale, killing hundreds, injuring thousands and leaving 100,000 people homeless.

The authorities took the view that it was impossible to rebuild Gibellina on the same ground that the earthquake had struck. A proposal was developed to build ‘Gibellina Nuova’ 10 kilometers south-west of the original town. The land for the new town was partially purchased from two notorious wealthy Mafia bosses, laying the foundation for a future fraught with corruption, compromise, and vested interests. Based on a butterfly motif and the extensive use of cars, the grand boulevards, and rigid, hierarchical urban plan of the town differed significantly from the organic, medieval streetscape of old Gibellina. In an interview carried out in 2018, local resident Calogero Petralia reflects on his relation to the new town: “Those postmodern buildings were not part of my tradition. I felt like an immigrant, four kilometres away from my real home.” 1

Construction began in 1971, but by 1979 little progress had been made. Meanwhile, the earthquake victims, members of an isolated agricultural community, were living in dire conditions nearby, within a skeletal infrastructure, substandard housing and scarce amenities.

In a bid to rescue flailing plans, Mayor Ludovico Corrao invited contemporary artists to submit proposals for artworks to populate Gibellina Nuova. With no budget and very little municipal support, Corrao held the belief that his ‘Mediterranean dream’ would inspire a new utopian network of relations and exchanges through the arts. His great proselytising skills proved an effective catalyst for action: he got international artists including John Cage and Philip Glass to perform in a festival, and even managed to convince the military to airdrop building supplies and help compact and enclose the rubble left by the devastation. Many artists and architects responded to his call-out, amongst them renowned Italian painter and sculptor Alberto Burri, who turned the invitation on its head and proposed a work for the site of the old town:

We went to Gibellina with the architect Zanmatti, whom the mayor had entrusted to look over the project. When we finally arrived … the new city was nearly complete and full of new pieces. ‘I can’t do anything here,’ I told him immediately, ‘let’s go see the old town’. It was almost 10 km away and I was just shocked. I almost felt like crying and then this idea came to me: here I could do something… This is what I would do: we compact the ruins – which are a problem for everyone – we reinforce them well, and with concrete, we create an immense white crack as a permanent symbol of what happened here.2

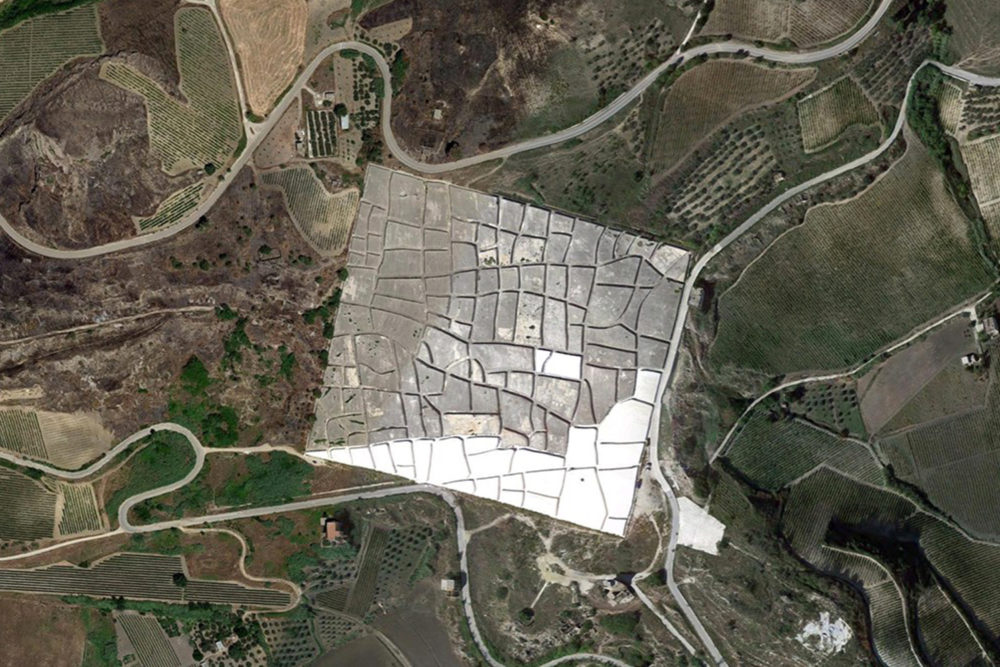

Burri’s memorial, Grande Cretto (Large Crack), takes the form of a labyrinthine 85,000 square meter concrete landscape which covers the footprint of the original town. The remains of the old town are coated in 10–20 meter wide, 1.6 meter tall, white concrete blocks which are interspliced with cracks that are big enough to walk through. These enormous fissures mirror the old town’s streets and corridors, conjuring spatial memories of the destroyed city, marking its status as an uninhabitable ruin.

The work, which is often heralded as one of the largest pieces of land art in the world, took thirty years to complete. It was worked on between 1985 and 1989 and then abandoned before an influx of state funds allowed construction to continue in 2011 and conclude in 2015 when it was formerly opened, twenty years after the artist had died. The two sections are clearly identifiable: the gleaming white concrete of later years form a sharp contrast to the more weathered, grey tones of earlier additions.

Today, half a century after the earthquake struck, Corrao’s radical experiment in civic engagement, rehabilitation and city-healing can be viewed as a cautionary tale. The architecture and artworks were met with much scepticism by the new residents who felt that this austere and inhospitable environment was foisted on them with scant regard for dialogue, engagement, or reference to architectural and social traditions built up over hundreds of years. Even the local priest, whose congregation was intended to occupy the centrally located, fantastically imposing Chiesa Madre (designed by architects Ludovico Quaroni and Luisa Aversa) refused to preach there, and a few years later, the roof collapsed. Other artworks and buildings were destroyed or moved by disgruntled locals. A town that was designed for 10,000 residents is today inhabited by 3,500. A ghostly, de Chirico-like atmosphere pervades.

A recent push to turn Gibellina into an ‘art town’ by restoring existing artworks and commissioning new ones, and raising its international profile, has resulted in an increase in cultural tourism. Festivals and exhibitions have been organised, websites launched, branding campaigns rolled out (the town was recently dubbed ‘the world’s largest open-air exhibition’) and a privately-funded foundation has been set up to sell the ‘concrete utopia’ narrative (‘Dream in Progress’ tours were offered throughout 2018). Grande Cretto is regularly used as a dramatic backdrop to fashion shoots, films, performances, and social media posts (Prada and Yves Saint Laurent have staged recent ad campaigns at the site). The extent to which the influx of visitors and this short-term, neoliberal approach to sustainability has benefited the lives of the inhabitants is a moot point. The fact that Mayor Corrao met a violent end when his young Bengali houseman murdered him with a blow from an ivory statue isn’t mentioned in the marketing brochures but it does form a grim reminder of the power structures embedded within the migrant workforce and the hierarchical makeup of the town.