Otwock, a small town on the outskirts of Warsaw in Poland, is home to a curious and unique collection of wooden buildings, known as Świdermajer. They made their appearance with the introduction of the Polish railway network towards the end of the nineteenth century, which facilitated travel from the city centre into surrounding areas. Otwock became a fashionable resort for the middle classes who relished the opportunity to attend to their health, take time out of the city, and to socialise during the summer months.

The idiosyncratic Świdermajer style combined local vernacular traditions with Swiss summer house features (wide roofs) and traditional Russian homes (wooden porches and windows), with ornamental additions taken from surrounding mountainous regions. These spas, sanatoriums, summer houses, and mansions are immediately identifiable by their extensive array of verandas, porches and balconies, designed to maximise residents’ access to fresh air and forest vistas.

In 1942, 75% of the Jewish population of Otwock (8,000 people) were assembled by the Nazis and transported to concentration camps in Treblinka and Auschwitz. The remaining Jews were shot. This harrowing episode in the town’s history marked the moment of its decline; it never regained its former self and the Świdermajer buildings fell into disrepair.

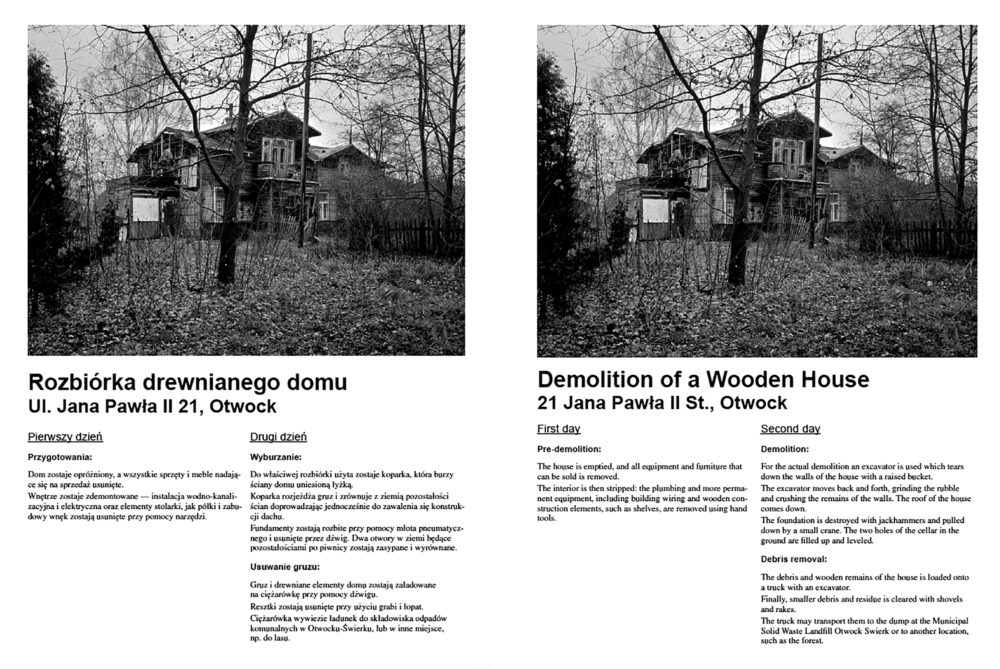

In 2011, at the invitation of curator Kasia Redzisz and artist Mirosław Bałka (whose family home is in Otwock), Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui developed a project that drew on the history of the Świdermajer buildings and their identity in the city. Many of the now listed buildings lay in a state of abandonment or ruin due to the prohibitively expensive cost of renovation and the bureaucratic formalities that lay in the way of demolition. The land upon which they sit has become increasingly valuable and a sizable number have perished through ‘accidental’ fires; many others were illegally demolished.

For Demolition of a Wooden House, Almarcegui selected one abandoned villa that was slated for demolition. She worked with a company that helped her describe the step-by-step phases of demolition that these buildings underwent, and catalogued this official process in text and photography form. This documentation was subsequently published in the local newspaper. The invisible, seemingly irrelevant process of demolition was now documented in a publicly acknowledged and archived format; the house’s disappearance presented as a sign of the inevitable process of destruction and renewal that is driven by the machinery of capitalism.

This reflection on the way that political, social, and economic change dictates the fabric of urban life strikes a melancholic tone which lies in stark contrast to the pared-down, factual mode of presentation used by Almarcegui in her newspaper article. Criticism of the process is implicit; transformation – in all its forms – inevitable.