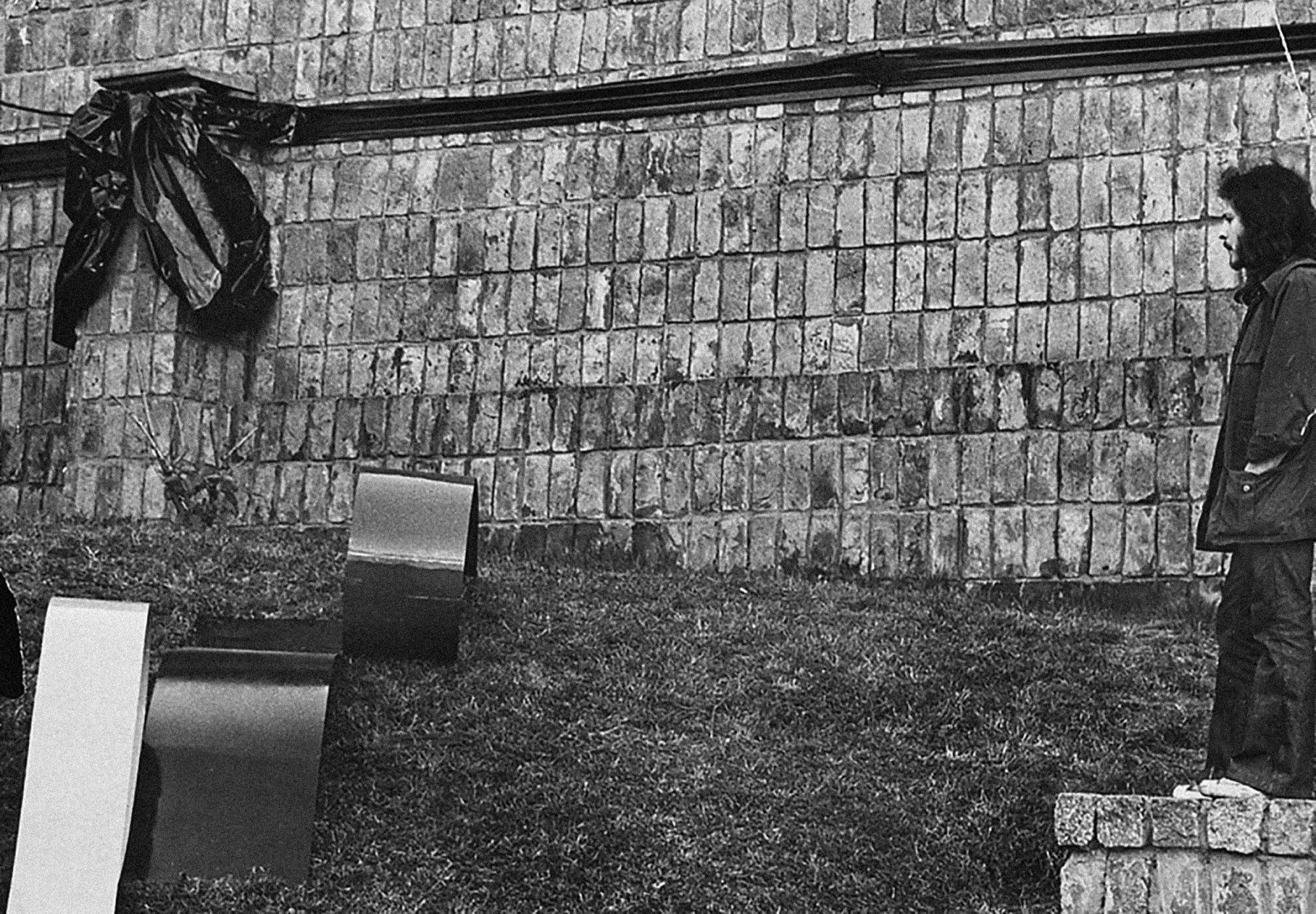

300 metros de cinta negra para enlutar una plaza pública (300 Meters of Black Tape to Mourn a Public Square) opened on 23 September 1972 at 4pm. Twenty-four hours later it had been dismantled by government officials. In the words of the artist, Horacio Zabala, it was ‘destroyed by the institutional vandalism of that era…not a single material vestige of the show remained, only references to it: the catalogue, the press releases…newspaper articles and a few photographic records’.1

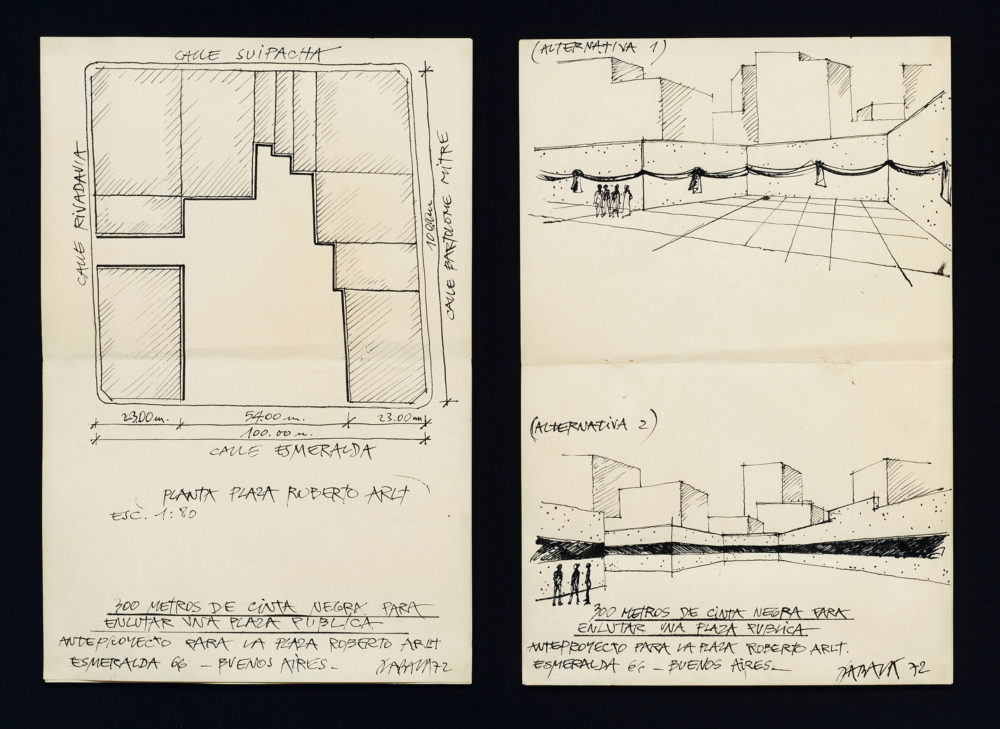

The work was part of an outdoor sculpture exhibition staged in Plaza Roberto Arlt, a very public location in the centre of Buenos Aires. By staging the exhibition in the public realm, the curator’s aim was to ‘take art to the streets and encourage new forms of collective reception and appropriation of art’.2 Zabala tied a black sash – replete with bows – around the outer walls of a large building, encircling the site in a sombre expression of public mourning. 300 meters… was a public memorial to a group of sixteen dissidents who had been brutally executed by Argentina’s military dictatorship a month before, in what became known as the Masacre de Trelew (Trelew Massacre).

In an era when overt displays of public dissent were punishable by imprisonment or even death, the work of artists, musicians, writers and poets became a crucial outlet. The subtle, often oblique ways in which the dictatorship was critiqued through art was a life-line for those in search of some kind of public expression of rage and sadness – and a determination that such violent acts would not remain unchallenged or unmarked.

Zabala’s work wasn’t the only installation that was destroyed that day; all the other works in the exhibition were also violently removed by police after the opening. The authorities initiated a court case against the curator Jorge Glusberg; a local, national and international outcry ensued, with many supporters of the exhibition, the artists and the curator, decrying the censorship.

Zabala set out his position on the social function of art in his Diecisiete interrogantes acerca del arte (Seventeen Questions about Art). In this manifesto of sorts, he made a passionate case for the potential of art to form disruptive interventions in the public realm and in so doing, become a catalyst for revolutionary action. One of the seventeen questions is directly applicable to 300 metros…: Can [art] offer a maximum of possibilities with a minimum of resources? A cheap, utilitarian, ‘non-art’ material (industrial plastic) is employed to make a poetic, radical statement about state-sanctioned violence and the importance of public resistance.

In 2012, Zabala carried out a re-enactment of 300 meters…, on the same building, giving the work the same title. The forty years that passed between ‘the original’ work and the ‘copy’ constitute, the artist says, a ‘temporal distance’:

The first instance of mourning can be considered a historical document that reflects a symptom of the violence prevalent during that era. The second expression of violence can be considered as the renovation of a past experience carried out in the present which entails contemporary values. As such, this work is or could be a mental reconstruction based on memory and imagination.3