On many levels, the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation’s City Sculpture Project of 1972 could be viewed as a fantastic failure. Designed to introduce the public to the latest developments in modern sculpture, the project sited fourteen artworks in towns and cities across England and Wales for a period of six months. Each work was offered for purchase to the cities in which they were located. None were bought, many were destroyed or ignored, artists got angry, the press had a field day. The paternalistic overtones of the project seep through into almost every aspect of the programme, but today, the collection of works and the responses to those works provide a valuable record of commissioning practices, attitudes to modern sculpture and site specificity, and our relation to the built environment in the latter part of the 20th century.

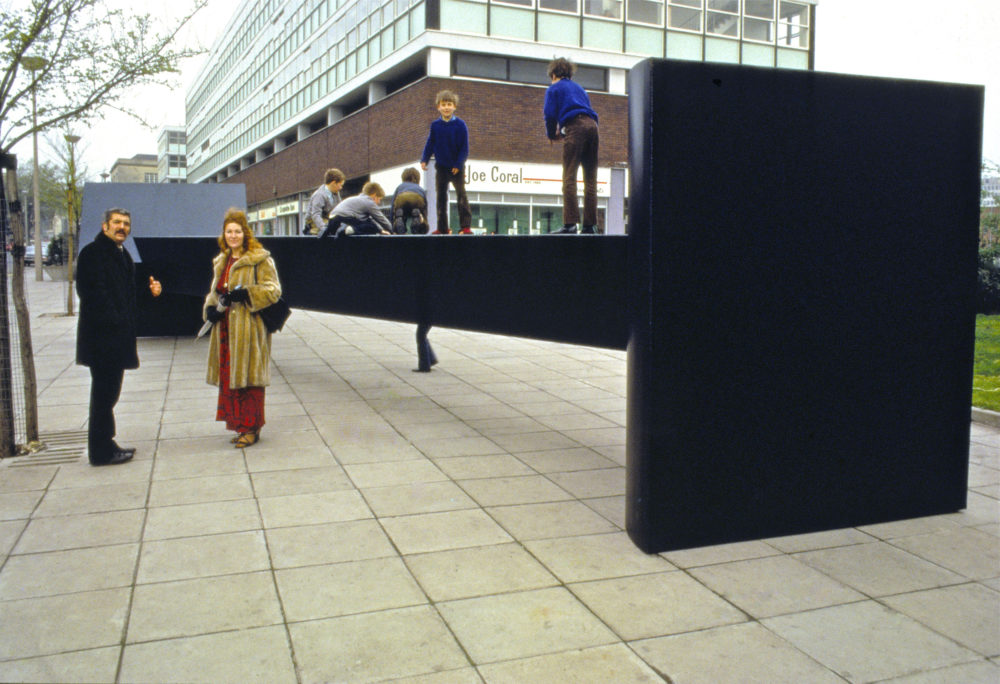

Garth Evans was one of the artists selected to show a work as part of the programme. Untitled Sculpture was sited in Cardiff, Wales for six months in 1972. It was extremely simple in form, consisting of three large, steel elements: two blocks (one a triangle, the other a half-cylinder) at the two ends of a long square section. It looked like a kind of bridge or mid-air tunnel. The artist later stated that the work was a memorial to the four-hundred and forty Welsh coalminers who died in the 1913 Senghenydd disaster.

Evans’ involvement in the programme reflected his interest in moving beyond the small confines of the commercial art world, a place he felt was ‘only useful to the wealthy and powerful’, towards a greater engagement with broader political, social and economic contexts. The seed of this desire was sewn in a placement he did in the late 1960s with British Steel as part of Barbara Steveni’s seminal Artist Placement Group.1

Evans was aware of the risks of ‘abuse’ to his sculpture but was adamant that the work would be experienced in a location where ‘people would come upon it naturally and interact with it rather than a more civic site that was controlled and institutionally sanctioned. He wanted to make an artwork that was monumental, ‘something that was charged with a sense of purposefulness… that speaks of a kind of useful power’. The bold form, he said, would ‘remain clear under any amount of graffiti and almost impossible to damage by climbing or playing on it’.2

The day after Untitled Sculpture was installed, Evans took a tape recorder to the site and interviewed local people, asking them to respond to the work. He didn’t tell them he was the artist; he was looking for unguarded viewpoints. The transcripts of those responses are a delight; together they constitute a beguiling snapshot of the mores and attitudes of the day:

What’s it supposed to be? Tell me, what is it? What’s the idea of putting it there? It’s a sculpture, and I suppose that’s modern art, is it? Well, isn’t art supposed to represent a thing..It’s better than anything else, anyway. I wish there were a hundred more like it.

It’s just art isn’t it?

I’m absolutely flabbergasted. I don’t know what it is (small laugh). What is it?3

Evans elected not to mention the fact that the sculpture was a memorial, or link it to any type of historical or familial narrative (many of his uncles were Welsh coal miners). He wanted the sculpture to be considered as a work of art rather than a utilitarian object – ‘a thing with a purpose’. As Evans recounts in a text written in 2015, ‘it was the absence of a reason for the sculpture’s existence…that seemed to be the source of discomfort…’. If an artwork is worthwhile, he said, ‘it needs to be able to disturb, confuse, and disorient’.4

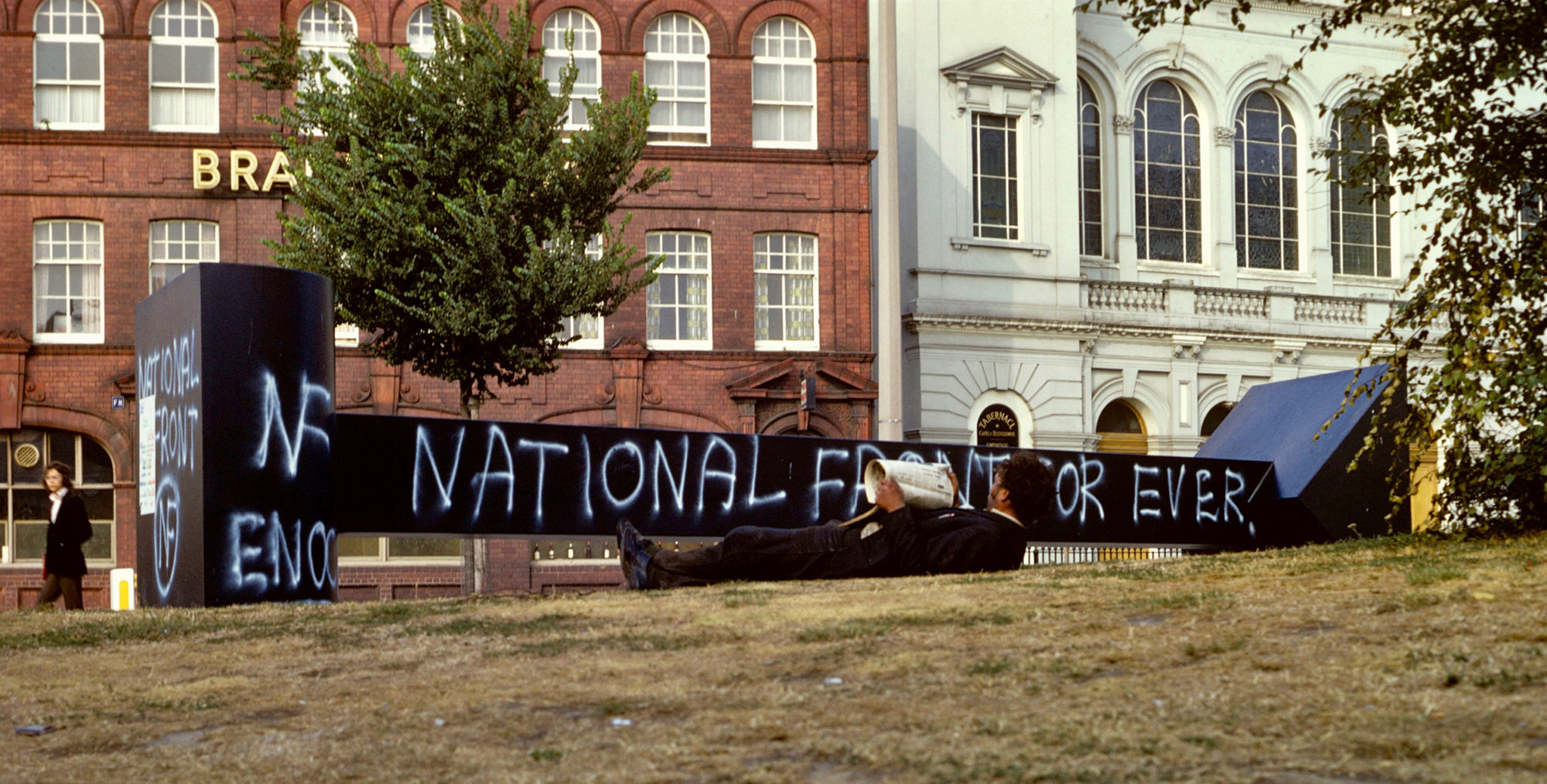

Not long after the work was installed, the following text was spray-painted along the central beam and two end points of the work:

ASIANS OUT / ENOCH IN

NATIONAL FRONT FOR EVER

In his Rivers of Blood speech of 1968, Enoch Powell raged against immigration to the UK and opposed the recently passed anti-discrimination legislation Race Relations Bill. He gave three speeches in Wales (one of those in Cardiff) in 1971, no doubt stirring up hatred and antagonism in the country.

When the City Sculpture Project was over, the graffiti on Untitled Sculpture was removed and the work was re-installed, 160 miles away, on the grounds of Charnwood College in Loughborough where it remained until 2019. During its time there, the sculpture was re-painted the wrong colour several times over, rust had spread across the surface, and a number of holes had developed around the base.

It was in a bad state when Chapter Gallery in Cardiff launched a campaign in 2019 to restore the work and bring it back to its original location after forty-seven years in the wilderness.

On 24 September 2019, after the unravelling of a complex web of issues relating to ownership, Untitled Sculpture was installed outside the Tabernacle Church in the Hayes, Cardiff. The original plan was for it to remain on site for six months, mirroring the period of time the work was originally installed in Cardiff. World affairs intervened however, and the six month period stretched to a year as the repercussions of a global pandemic played out.

To coincide with the return of the work, Chapter Gallery bought a theatrical production of the general public’s responses to the sculpture, as originally recorded by Evans in 1972, to the city of Cardiff. Written by American writer and poet Leila Philip in collaboration with Evans, The Cardiff Tapes had opened on Broadway in New York a few years earlier, in 2017. The narrative and set picked up on the racism and xenophobia displayed in the graffiti (ASIANS OUT was splashed across the back of the stage), and took the audience on a journey from the 1970s to the present day, ruminating over political and cultural conflict, the multiple interpretations of the work, and society’s often strained relation to contemporary art.

In September 2020 Untitled was gifted to the University of Wales, which, fittingly, once incorporated the South Wales and Monmouthshire School of Mines.