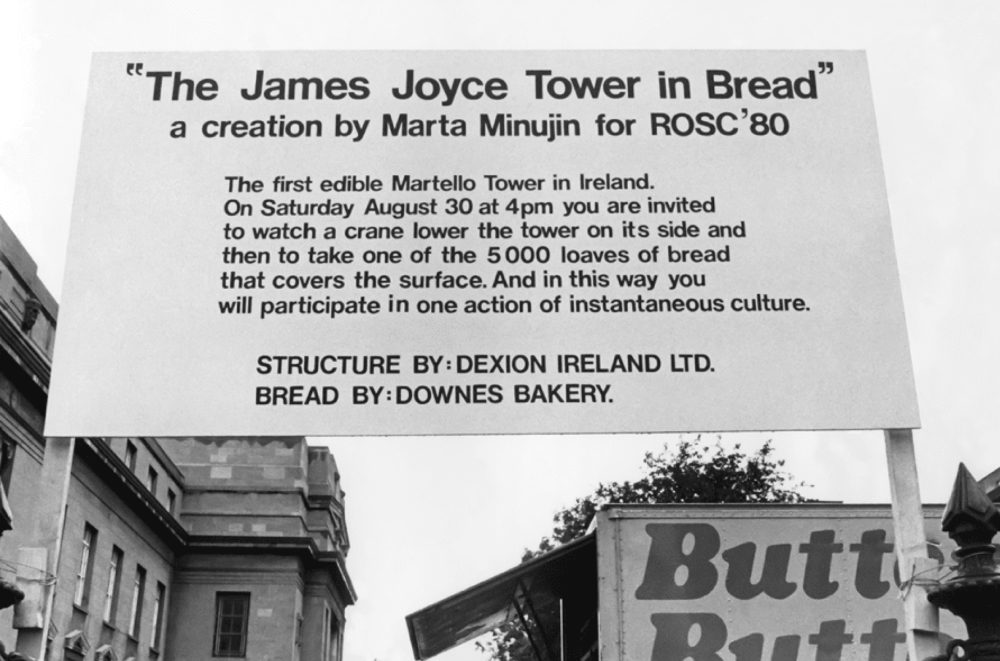

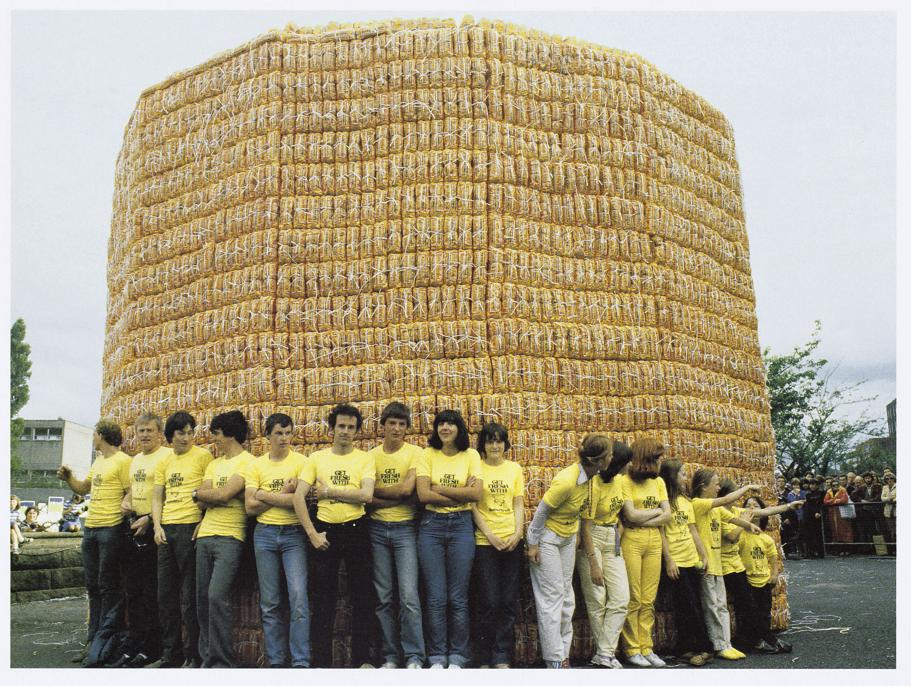

In the summer of 1980, a temporary sign appeared in the streets of Dublin inviting people of the city to take loaves of bread from an ‘edible Martello Tower’. At 7am on 30 August, a fleet of vans arrived, carrying 5,000 freshy baked loaves of Butterkrust bread from Edmund Downes’ bakery, a much loved local shop referred to by James Joyce in Dubliners (1914). Fire engines followed in their wake, and employees of the bakery ran up and down a portable scaffold system erected by fire fighters, attaching each loaf to an enormous metal structure measuring 8.5 metres high, 11 metres across, which took the form of a Martello tower (another Joycean reference, this one from Ulysses, 1922). A group of volunteers wearing handsome yellow T-shirts assisted the process. Nine hours later, at 4pm, a crowd began to gather. Expectation and bemusement swelled the city streets. A crane manoeuvred into position and fastened a hook to the frame of the tower, hoisting it up then laying it down on its side. Members of the public were invited to strip the structure bare and take home free bread.

Mayhem ensued. Those with a head for heights climbed up the frame and threw hundreds of loaves onto the crowd below. Housewives, artists, local kids, representatives of charities – all clambered for a bit of the action. Various attendees attempted to control the proceedings by informing people that there was plenty of bread to go around. The Argentine ambassador was pelted with bread from a section of the crowd yelling ‘fascist!’, while a select band of dignitaries sipped champagne from the side lines. An Alderman was interviewed by the local press: “I think it’s a great idea” she said, “The bread will be eaten and the Martello Tower will never be the same.”1 Others thought it was a terrible waste and gathered loaves to take to those in need.

The scene was orchestrated, with the use of a megaphone, by Argentinian artist Marta Minujín who had been invited to make an artwork for ROSC ’80, an international exhibition that took place every four years in venues and outdoor settings in the city.

For many, Minujín’s work was a straight forward exchange: in return for their participation, they got to take home free bread. For others, it was a reflection on materiality, consumerism, communal action, and even Catholic transubstantiation. Some played with the idea that by making the vertical horizontal (laying the tower on its side) and rendering it edible, the artist was devaluing the symbolic power of the tower. Philosopher Richard Kearney suggested that the purpose of the happening was to ‘annihilate the notion of art as an autonomous activity displayed in galleries and museums’. He seemed perturbed that by collapsing the divide between the uniqueness of art and the uniformity of consumer society, the artist would be ‘divesting her work of its radicality and emancipatory power’. Like Warhol’s paintings of soup cans, he argued, that this ‘self-defeating artwork succumbs to the everyday world of consumer exploitation which radical art is able to subvert’2. Art critic Jorge Glusberg took a more positive view and focused on the democratic inclusivity of the work:

James Joyce’s Tower is sculpture, a process sculpture – it was inaugurated standing, it became the protagonist of activity, and it ended up on the ground to finally disappear, despoiled of its basic materiality. In a sense, though, it lived on in the rolls the spectators took home with them until they were all eaten…in this way the rolls became res publica, that which belongs to everybody.3There are whispers that the infamous American art critic Clement Greenberg attended the event, but no documentation exists indicating his response. One enthusiastic child asked the artist ‘Didja bring any butter, missus?’ and the French art critic Pierre Restany proclaimed his support for the work by stating that it was neither an insult to Joyce, or to bread! Local journalists had a field day (To build a tower, says Martha, use your loaf!) and Marta Minujín herself told a local journalist that she thought the response was wonderful – it is instantaneous culture. The important thing is, when people eat the bread.4

A few years later, Minujín continued this line of joyful, destructive enquiry by installing a replica of the Parthenon in Buenos Aires and covering it with 20,000 books that were banned in the 1976-83 military dictatorship. Audience members were invited to take the books home with them when the work (called El Partenón de los Libros) was dismantled, thereby gaining access to reading material that had been denied to them for years.

Throughout her sixty year career that spans the 1960s to the current day, Minujín has developed a reputation for her hugely ambitious, often quite bizarre participatory, publicly sited artworks, happenings, installations and performances. Viewed by some as ‘Latin America’s answer to Pop’ she is interested in shifting people’s perception through processes of transformation, destruction, and experimentation.

In 1963 she staged a happening (La Destrucción) in the grounds of a Paris gallery. Things got out of hand when she invited audience members to consider the ‘death of art’ while she burnt her work and freed hundreds of birds and rabbits from their cages. A few years later in a Buenos Aires gallery she caused a media frenzy with her ambient, labyrinthine, walk-in piece made in partnership with artist Rubén Santantonín called La Menesunda (Mayhem) in which audience members were bombarded with sensorial stimuli. She installed a phone booth in a New York gallery that, depending on the number dialled, produced a Polaroid shot and nine effects including smoke, helium, breeze, and coloured water.

Her work has been greeted with enthusiasm, outrage, and bemusement. Today, it can be viewed as a precursor to much contemporary art practice that involves large audiences, experiential, immersive environments, and a sophisticated understanding of the power of seduction, mass media and technology.