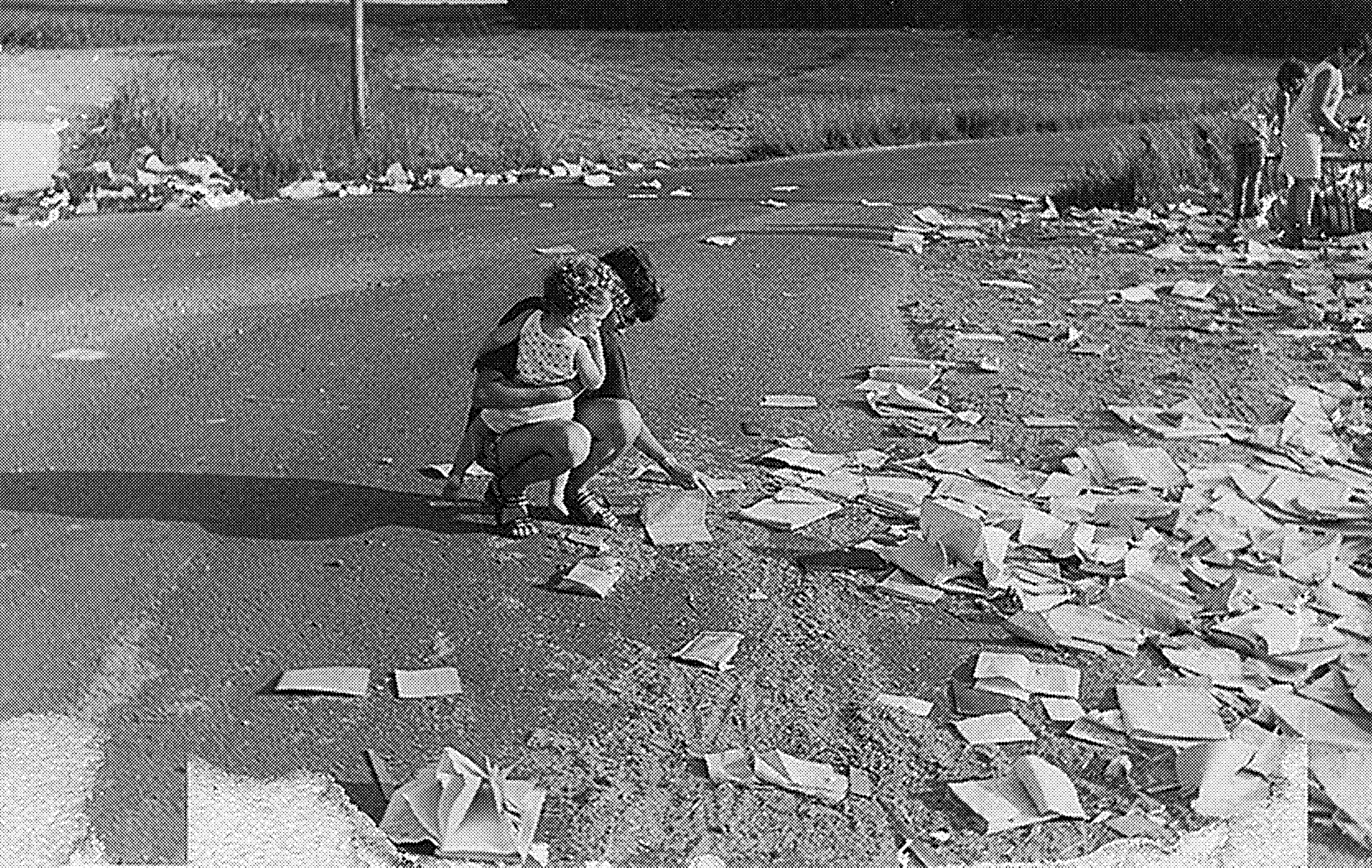

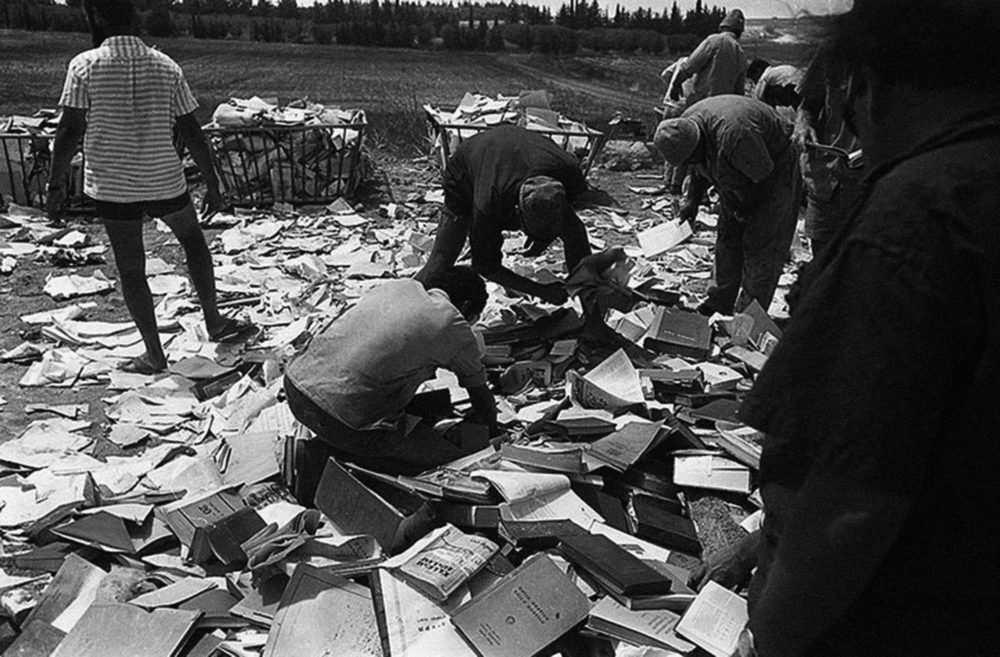

Over a three month period in 1972, Israeli artist Avita Geva, along with a group of other artists Moshe Gershoni, Michah Ulman and Yechezkel Yardeni, collected thousands of second-hand books and loaded them into large cattle-feed troughs on the strip of land separating a Jewish kibbutz and an Arab village. Photographs show Israeli men in shorts and t-shirts, mothers with children, a Palestinian man wearing a keffiyeh, sifting through the books, stuffing some into their pockets, leaving others scattered across the land.

These physical, perishable objects that form the cornerstone of Jewish culture eventually began to rot and fold back into the earth, becoming part of the cycle of organic life. Can these books serve as cultural and social fertilizer, creating the conditions for interaction between Jews from the kibbutz and Arabs from the nearby village? Or perhaps they can be seen as the reverse of a ‘land-grab’ – sharing knowledge and renouncing the concept of possession, demonstrating the futility of chasing after ownership and control. In their fragile, pathetic state they may well indicate the possibility of viable coexistence but they could also highlight the process of deterioration inherent in something that is about to expire.

Not long after making this work, Geva left the art world to pursue a more direct route to social, environmental and political change. His Ecological Greenhouse project, founded in 1977, began as an experiment in gardening and gradually expanded into a multi-disciplinary research and education centre for surrounding communities and schools which continues today. In 1992, Geva temporarily re-entered the embrace of the art world when he represented Israel at the Venice Biennale, with his Greenhouse project.