When Tina O’Connell and Neal White carried out a residency at the Limerick based arts organisation Askeaton in 2017 they looked into the history of the nearby Ardnacrusha Hydro Dam and Power Station. Remarkably, the building was depicted in a mural in the Irish Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Visited by 44 million people, the Fair celebrated an idea of ‘the world of tomorrow’ with its adopted slogan ‘Dawn of a New Day’.

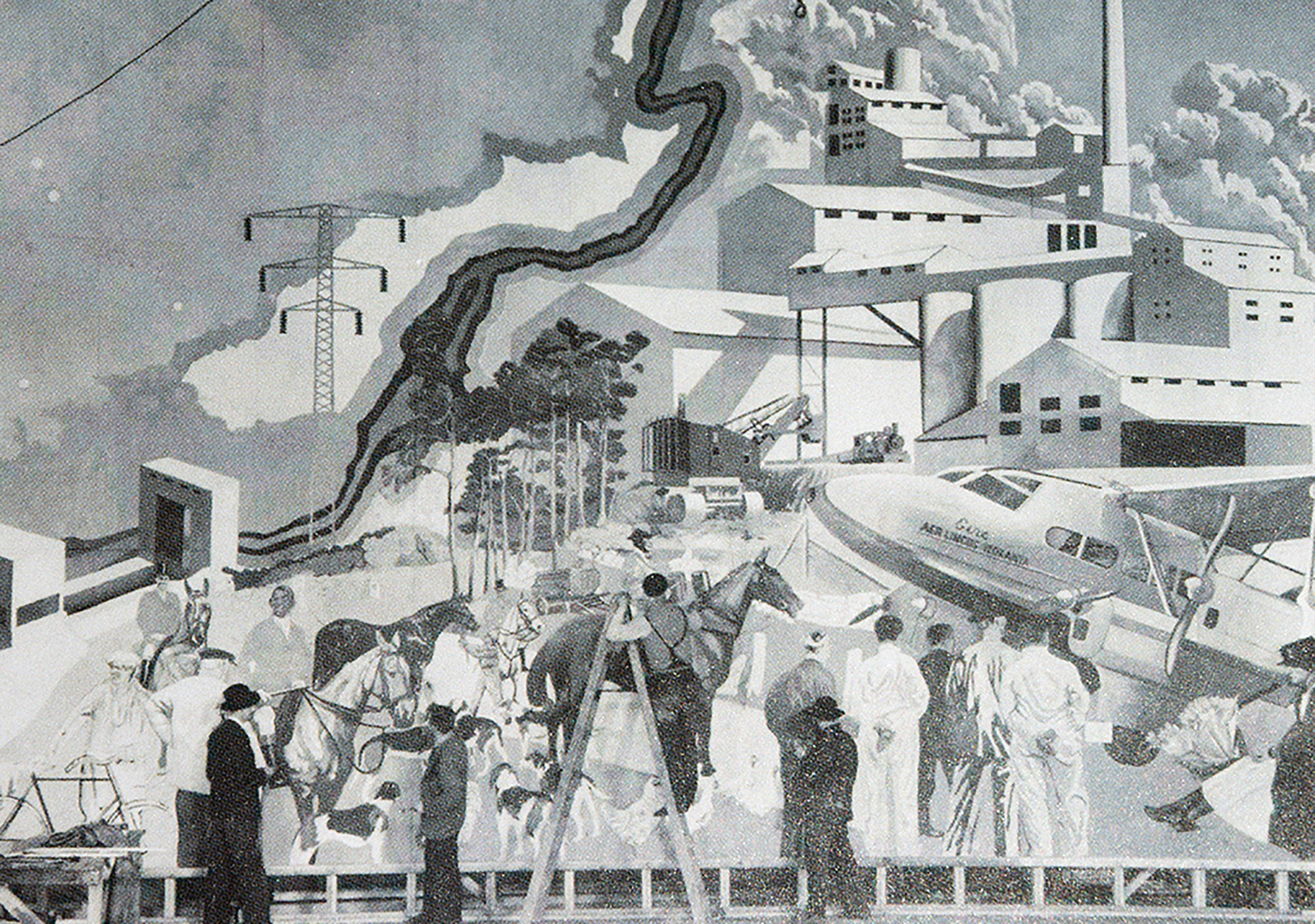

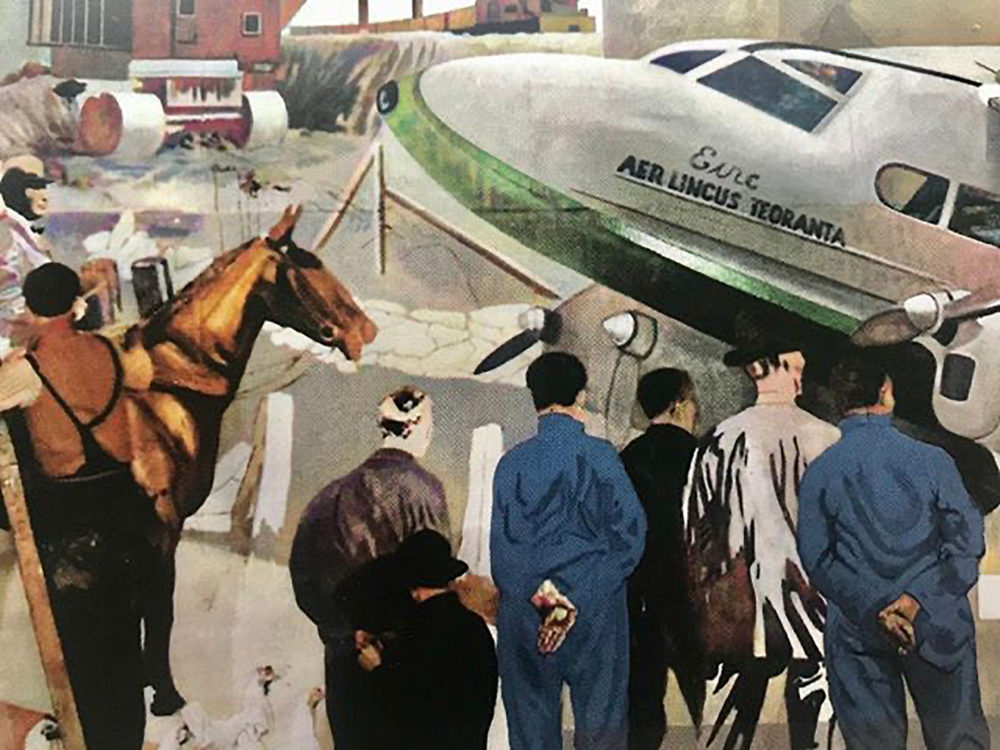

The romantic realist, Limerick-born painter Seán Keating, was commissioned to paint the mural. Keating had become known for his depictions of Irish life and labour and his deep commitment to the development of the Republic of Ireland. His mural for the Irish Pavilion positions Ireland as a pioneer of modern technology, looking towards the future, with the power station at its centre. In a contemporary style that deviates significantly from previous work, Keating points to advances in aviation and telecommunications as well as Irish independence (the power station opened to significant fanfare seven years after independence from British rule in 1922).

When the World’s Fair ended, the Irish government refused to pay the three hundred dollars required to dismantle the panels and return them to Ireland. In 1941, two years after the Fair had taken place, the artwork was destroyed, along with the pavilion. No doubt, the fate of many of the pavilions was overshadowed by the events of World War II. Very little photographic documentation of the work exists today, but Keating did leave a few notes which provide details of his painting process, with particular reference to the colour palette (‘Buff Yellow, Map Green, Burnt Umber, White, Red and various shades of Blue’). There are whispers about the existence – in a private collection – of a short 16mm film of the work, but these have not been substantiated.

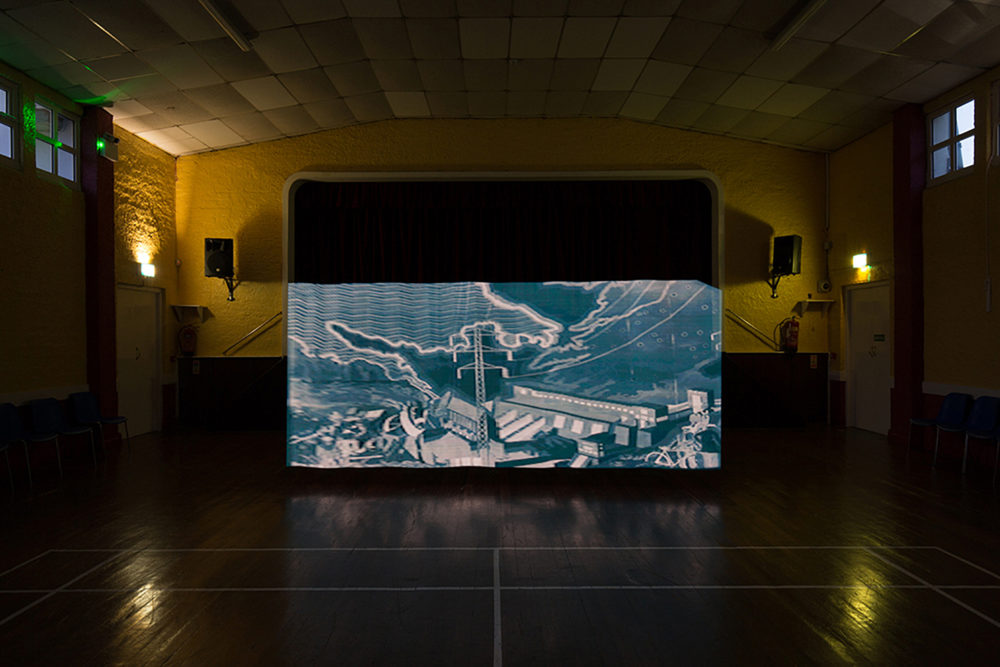

For their contribution to Askeaton’s 2017 festival of contemporary art Welcome to the Neighbourhood, O’Connell and White mapped the floor-plan of the Irish Pavilion onto the floor of the local community centre and, using pixelstick technology (a sophisticated LED light painting tool that comes alive in dark spaces), they reconstructed Keating’s mural, working with the few low resolution photographs they had managed to locate in their research. The aim was to ‘bring the mural home’, and to introduce the story to a new audience.

The artists staged a further series of ‘spectral reconstructions’ of sculptures by artists Helen Chadwick, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth that have been lost or stolen from public sites across the UK. The works appeared as apparitions at twilight, transposed to a new home, bringing sculptures of international repute to a small Irish town.

Through this exploration of loss and rejuvenation, O’Connell and White’s on-going project seeks to recalibrate the narrative of an artwork, creating new locations, contexts and eras in which it is able to exist.