Each time John Latham was asked why he set fire to a column of books, he had a different answer. One of his responses went like this:

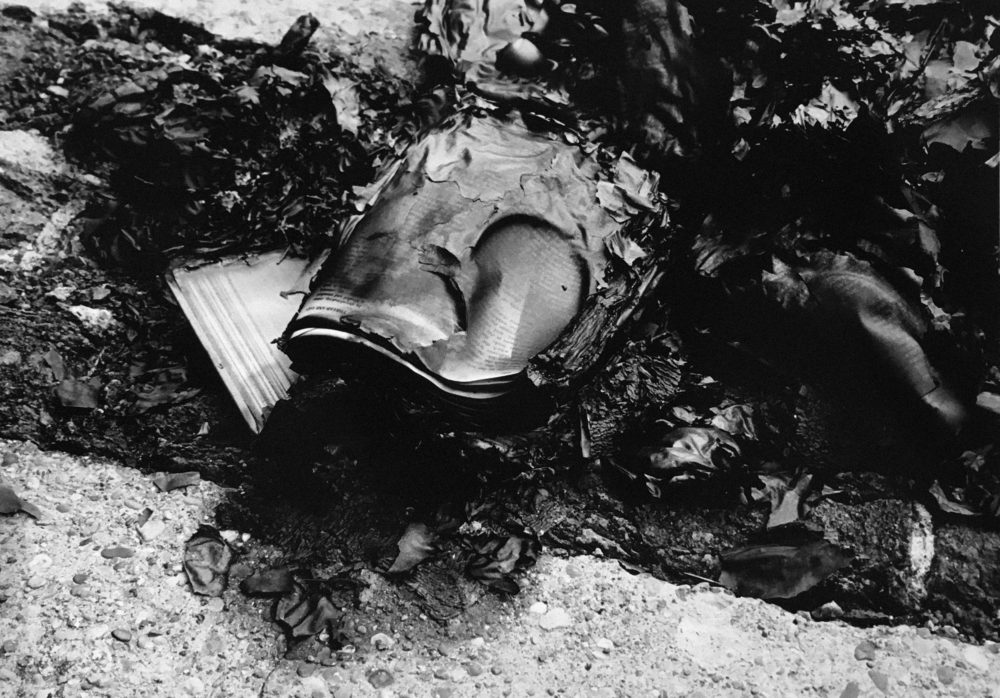

It was not in any degree a gesture of contempt for books or literature. What it did intend was to put the proposition into mind that perhaps the cultural base had been burnt out.1Other responses positioned the performances as an attack on institutionally acquired knowledge and received opinion which Latham called the ‘Mental Furniture Industry’ and ‘false truths’. He was deeply critical of certain books which he felt stifled intuition and unreflective thought. Some critics saw the performances as anti-intellectual or even fascist acts of iconoclasm. In recent years, they have been considered within Latham’s Time-Base Theory as ‘events’ in time which reveal multiple temporalities and a new way of understanding the world.2 Whatever the interpretation, it’s clear that the towers invert the traditional function of literature which is typically read in a linear and temporal manner, and we are left with an object that is consumed spontaneously, without structure or pre-conceived knowledge.

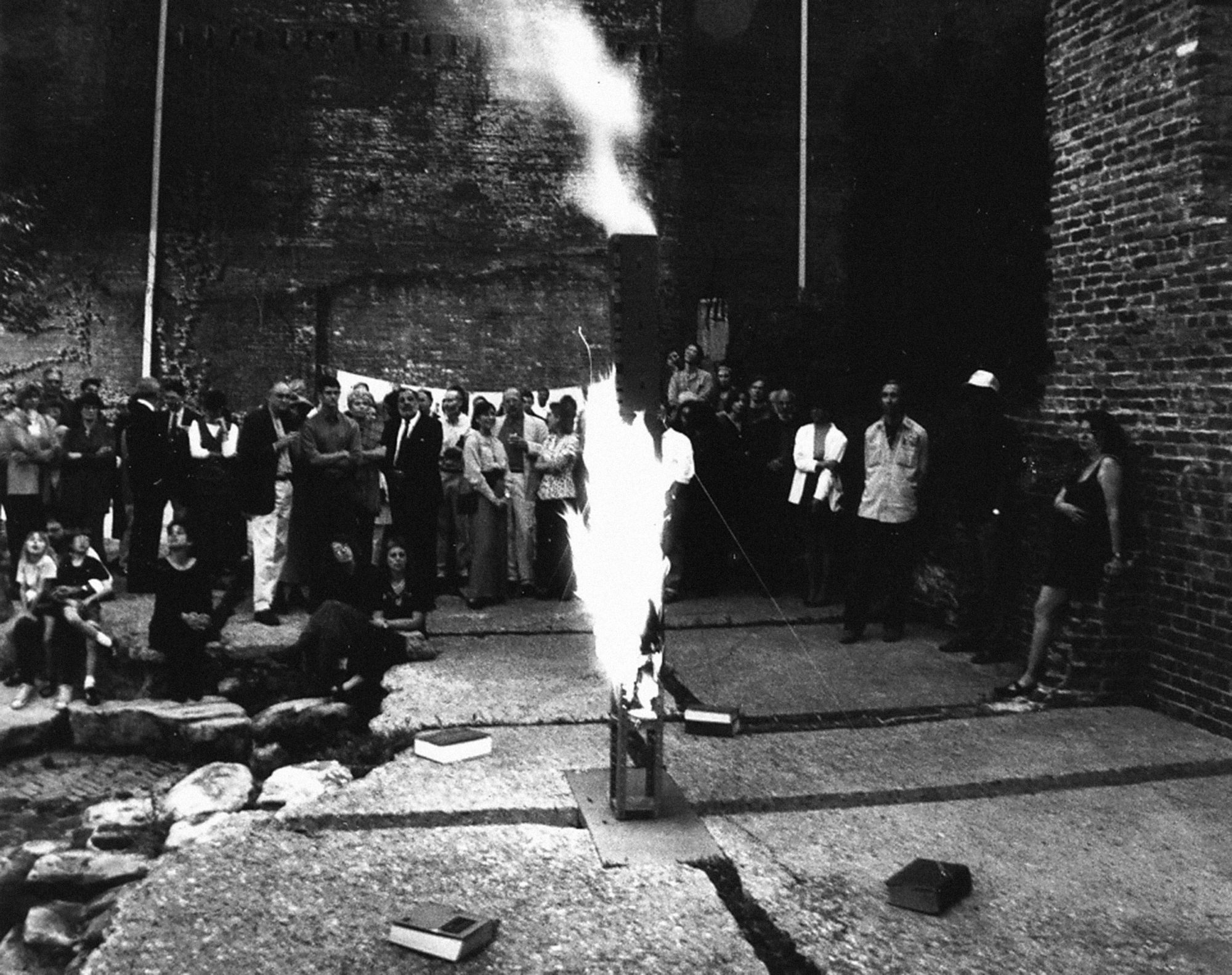

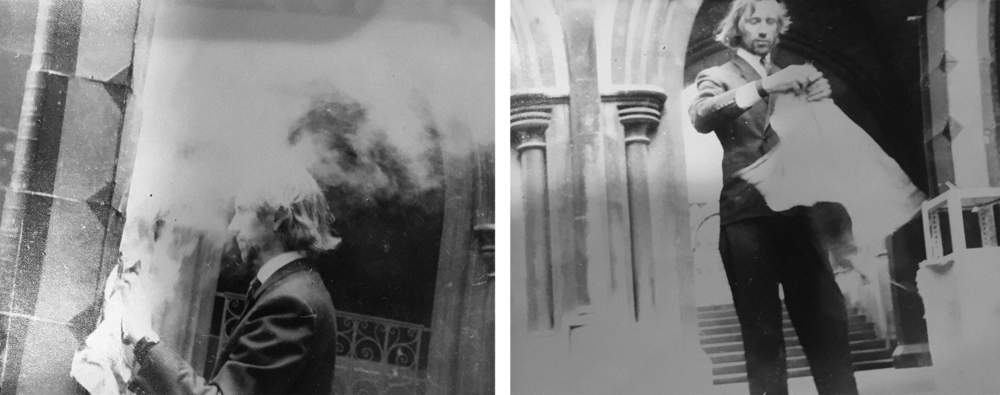

Latham produced six towers, most of which were around three metres high. Each one was made up of interleaved reference books and magazines (often encyclopaedias) which were stacked on top of a metal framework and plinth. These improvised chimneys were set alight at the base, often in or near conceptually loaded public spaces whose identity is based on institutional power and historically sanctioned knowledge, such as the Law Courts, British Museum, Houses of Parliament, and Senate House.

The first of Latham’s ‘Skoob Tower Ceremonies’ (‘skoob’ is books spelt backwards) took place in 1964 in Braziers Park, Oxfordshire, with a group of like-minded artists, poets, filmmakers and thinkers (the anti-psychiatrist R D Laing was purportedly present). Latham staged the penultimate performance on the Southbank in London where two towers were burned and photographs were taken to publicise Gustav Metzger’s now infamous Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS) in September 1966.

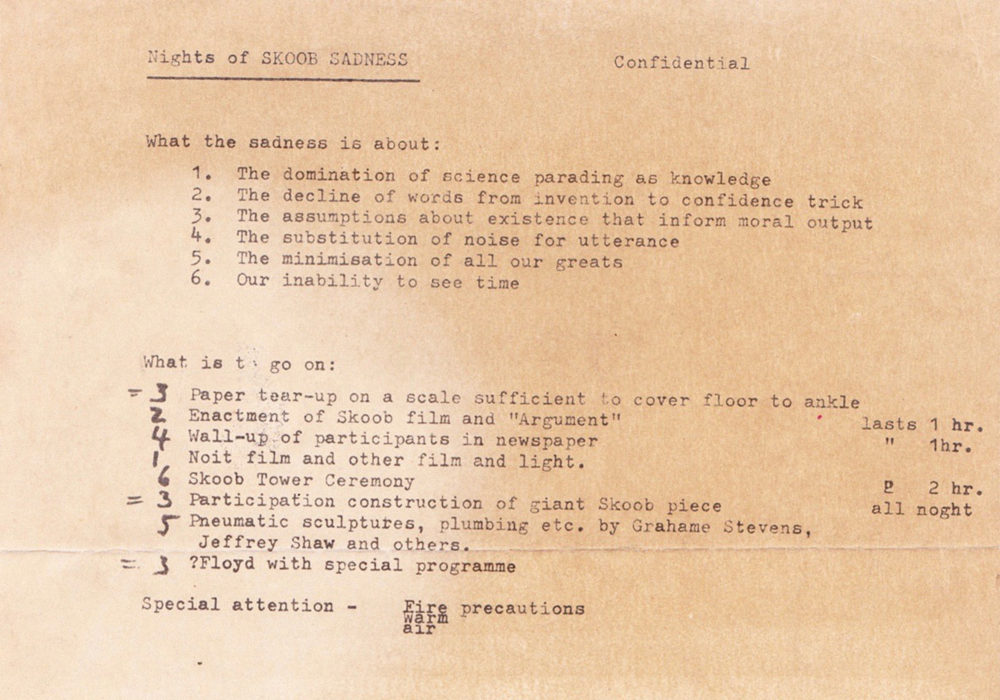

There’s a document in the John Latham archive, held at Flat Time House, (his studio home in south London which is now a gallery and ‘living sculpture’) called ‘Nights of SKOOB SADNESS’. It appears to be a plan for a series of happenings which took place at Better Books in 1967. Here Latham lists six reasons that he is sad. They range from ‘The domination of science parading as knowledge’ to ‘Our inability to see time’. He goes on to attempt to fix the problem with a list of eight actions which include ‘Paper tear-up on a scale sufficient to cover floor to ankle’ and ‘Skoob Tower Ceremonies’.

In 1967 Latham cemented his reputation for scurrilousness when he was sacked from his teaching post at St Martin’s School of Art for chewing up and spitting out a library copy of critic Clement Greenberg’s collection of essays Art and Culture (1961). He took umbrage at Greenberg’s emphasis on the formal content of art and objected to his dismissal of British art being too tasteful. Along with a group of students, Latham collected the masticated balls together and left them to ferment using various chemicals and yeast. He returned the phial containing the distilled ‘essence’ of Greenberg to St Martin’s library. Still and Chew: Art and Culture 1966–1969 is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.