American artist Sam Durant made his sculpture Scaffold for Documenta (13) which took place in Kassel, Germany in 2012. Two years later, the work was shown at Jupiter Artland near Edinburgh in Scotland. Neither installations caused a ruffle amongst audience members who climbed the stairs, admired the view, read the accompanying text.

In 2017, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota showed the work (which had been acquired for their collection) as part of a programme of sculptures designed to celebrate the re-opening of the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. Other works in the programme included Katharina Fritsch’s giant blue rooster, Hahn/Cock (2013), and Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s iconic Spoonbridge and Cherry (1985–1988).

Scaffold was a fifty foot tall, unpainted wood and steel structure that resembled an interactive gym jungle with its array of stairways, posts and platforms. Its design was, in fact, based on the gallows used in seven high-profile executions that took place in the US between 1859 and 2006, including the abolitionist leader John Brown (1859), four anarchists in Chicago in 1887, and deposed Iraqi president Saddam Hussein in Camp Justice, an Iraqi-American military base in Kadhimiya, Baghdad (2006). Importantly, the sculpture also referenced the US’s largest mass execution which took place, under the order of President Lincoln, in Mankato, Minnesota in 1862, in which thirty-eight Dakota Indians died.

Durant’s stated intention was to open up a debate about the histories of racial injustice embedded within the criminal justice system in the United States, involving lynchings, mass incarceration and capital punishment. In Kassel and Edinburgh, this was an academic exercise viewed by predominantly white audiences who were one step removed from the subject matter. In Minneapolis, where the 1862 executions had taken place, the context, history, and ‘audience’ represented an entirely different set of circumstances.

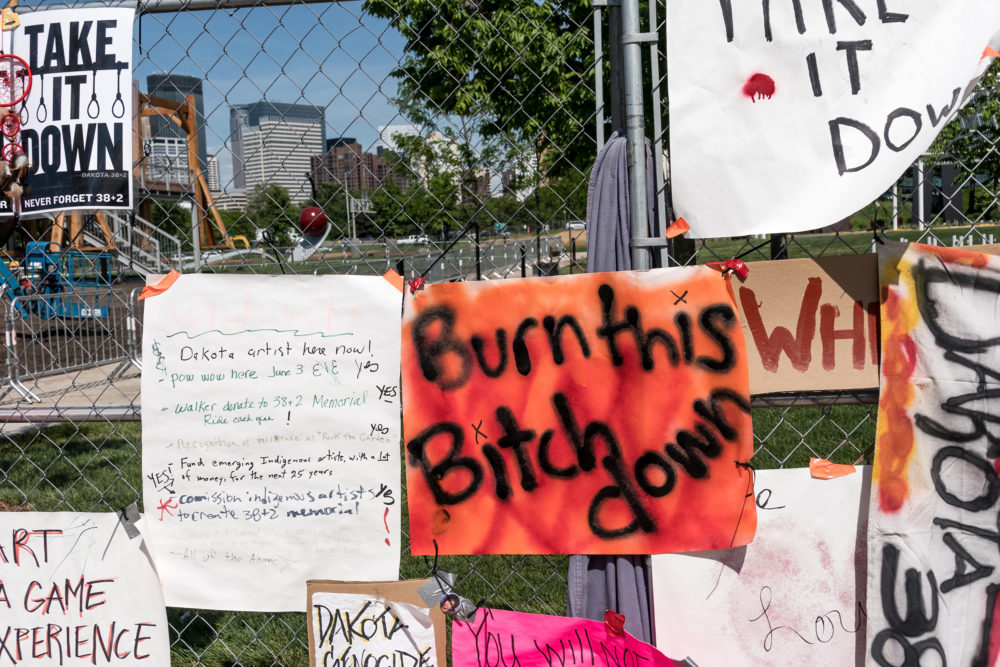

The rapid escalation of events surrounding the proposed installation of Scaffold in Minneapolis began with a statement from the Walker Art Center’s executive director, Olga Viso, on 25 May 2017. Viso outlined the curatorial approach and selection procedure for the eighteen new sculptures, which were due to be unveiled on 3 June. The following day, members of the Dakota community gathered at a chain-linked fence, close to Durant’s sculpture, to protest against the installation of the work. Interviews with protestors were beamed across the world through TV channels and newspapers:

It’s really traumatizing for our people to look at that and have it just appear without any warning or idea that they were doing this. And it’s not art to us.1 It truly saddens me that in 2017, we still live in a world where the intergenerational trauma of a people can be put on display for the world to see without any consequences.2 It needs to come down in a way that is healing and not destructive.3

Placards attached to the fence reinforced the message:

Execution is not art

Not your story

TAKE IT DOWN

Our generation is not your art

Viso posted an open letter to The Circle, a publication devoted to Native American news and arts, outlining the Walker’s intent and acknowledging potential concerns with the work’s reception, particularly amongst local Native audiences. She established a route of communication between community members, the artist, and the museum. The following week, on 31 May, after a three-hour meeting between these groups, the Walker announced that Scaffold would be dismantled that day, and the wood would later be burned, at another site, in a private Dakota ceremony.

Durant issued a statement outlining his regret at not considering the broader implications of showing the work in Minneapolis:

Your protests have shown me that I made a grave miscalculation in how my work can be received by those in a particular community. In focusing on my position as a white artist making work for that audience I failed to understand what the inclusion of the Dakota 38 in the sculpture could mean for Dakota people… My work was created with the idea of creating a zone of discomfort for whites, your protests have now created a zone of discomfort for me.4Durant transferred the intellectual property rights of the work to the Dakota people and agreed never to create another piece based on the Mankato scaffold. In a conversation with Viso, he reflected that:

…the ways in which this process unfolded allowed me to transform Scaffold with the help of the Dakota (and the media) into something that will have a far greater impact in society and be closer to my original intentions than if the work had remained as it was constructed in the sculpture garden.5The Minnesota newspaper Star Tribune arts reporter, Alicia Eler, asked writers and critics from across the US for a response to the controversy. Some, including Aruna D’Souza, academic and writer, were supportive of the way the artist and museum director had dealt with the situation:

The controversy around Scaffold is one of the few times I’ve seen these difficult conversations actually come to pass in a useful, thoughtful, and productive way – and it happened because Sam Durant and the Walker were able to recognize that listening is an essential part of speaking freely. This is how discourse should work. If we’re smart, we’ll come to see this process – the construction of the piece, the protests, the mediation, as well as the ceremonial destruction – as one of the most important social practice art works of our time.6Others were critical of the privileging of the white male artist, predominantly white institution, and white audiences. Jerry Saltz, the infamous art critic of New York Magazine was characteristically blunt:

In general it’s time for all of us to shut up and listen. The work wasn’t that good in Documenta either. The real problem with it is that ALL its supposed content is in the work’s explanatory wall label. The work itself is meh-sensationalism. Male fixation on big death.7This turbo-charged lesson in contextual, ethical commissioning forces a range of questions: What happens when the same artwork is installed in different cities, embedded within different histories and communities? What is the role of the artist and to whom are they responsible? What are the consequences of (white) artists and arts administrators putting themselves at the centre of a story about race, forgetting about privilege, inclusion and social equity?

The local, national and international outcry, coming just a month after the furore surrounding the inclusion of Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till in the Whitney Biennial, addressed the subject of cultural appropriation, white supremacy, and blind curating. New Yorker journalist Andrea K. Scott addressed another problematic resonance: ‘the current suicide rate among Native American teenagers is the highest of any population in the United States. As the Sioux elder Sheldon Wolfchild told the Minneapolis Star Tribune, ‘Just the other day, we had a memorial for a twelve-year-old girl who strangled herself with a rope. What happens when a young boy or girl looks at that [sculpture] and is giving up?’ (New Yorker, 3 June 2017). Scott got to the nub of the matter when she wrote: The dispiriting truth, as both Durant and the Walker’s Viso have conceded …, is that they failed to imagine an audience for Scaffold that wasn’t white. (New Yorker, 3 June 2017).

Olga Viso resigned from her position as executive director of the Walker Art Center soon after Scaffold was dismantled. In 2019, the center launched an open-call directed at Native artists for a public art commission to be located at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden or the Walker campus. Angela Two Stars was appointed; her artwork (Okciyapi, 2021) is a gathering site for people to engage with the Dakota language, culture and traditional teachings. This initiative was part of a number of commitments made by the museum to Dakota elders during the mediation process that led to the removal of Durant’s sculpture.