It took twenty-four years for Christo and Jeanne Claude to realise their ambition to wrap the Reichstag in Berlin. It started in 1971 with a suggestion from American journalist Michael Cullen who was based in Berlin, and the project was launched in the summer of 1995.

Christo defected from communist Bulgaria to Austria in 1957 (concealed in a truck with fifteen other deserters) – an act that no doubt affected his decision to work on a project that addressed the subject of east-west relations.

The Reichstag at that point was a partially ruined former headquarters of the German Empire, loaded with symbolism and a complex array of historical baggage. It was built in 1894 in the neo-classicist tradition, gutted by fire in 1933 (some say by the Nazis), and extensively damaged in World War II. In 1961, when the Berlin Wall was constructed to divide West Berlin from East Berlin and surrounding East Germany, it ran along the back of the Reichstag. Throughout the Cold War, the building came under the jurisdiction of both East and West Berlin authorities.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude worked with six different presidents of the Bundestag and applied for permission to wrap the Reichstag three times; each time they were refused. The unfathomably complex set of negotiations that the artists and their team entered into in order to realise the project was extraordinary and could be spoken of as a type of mania (Christo acknowledged that the project was “absolutely, totally irrational”).1 The fact that the title of the work includes the dates that the artists spent working on the project is a clear indication that they saw the process leading up to the wrapping, as well as the wrapping itself, as the artwork – with all its political, administrative, absurdist wrangling.

Things became more achievable with the reunification of East and West Germany and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 but Christo and Jeanne-Claude still needed to get British, American, French and Soviet military forces to all agree to their proposal (the Reichstag existed within the British sector of occupied Berlin, while its eastern façade lay within Soviet controlled air space). In February 1994 the president of the German parliament Rita Süssmuth intervened on the artists’ behalf and escalated the process, establishing a parliamentary vote. This was the first time the fate of an artwork had been decided by the nation’s parliament. Germany’s tumultuous past and the reverberations attending the fall of the Wall meant that the supercharged political and historical significance of both the building and the proposal was greeted with fear and scepticism by politicians.

There was an unusually high turn-out of 525 members for the debate on 25 February 1994. It was televised and viewed by millions. The motion was passed on the grounds that this was “simply an art project with no hidden message”, that it would be paid for privately through $15.3m sales of the artists’ editions, drawings and models, and that all materials would be recycled (swatches of the fabric were distributed amongst visitors) – a kind of ‘hands up, nothing to do with me’ type of acquiescence.

When a Neo-Nazi group got wind of the Parliament’s decision, they wrote to a German newspaper threatening to kill Christo if the project went ahead. Each time Christo visited Germany from that point on, he was protected by numerous body guards and instructed to wear a bullet-proof vest. Jeanne-Claude insisted that Christo gave a sample of his blood to a local hospital, in the event that he required a transfusion.

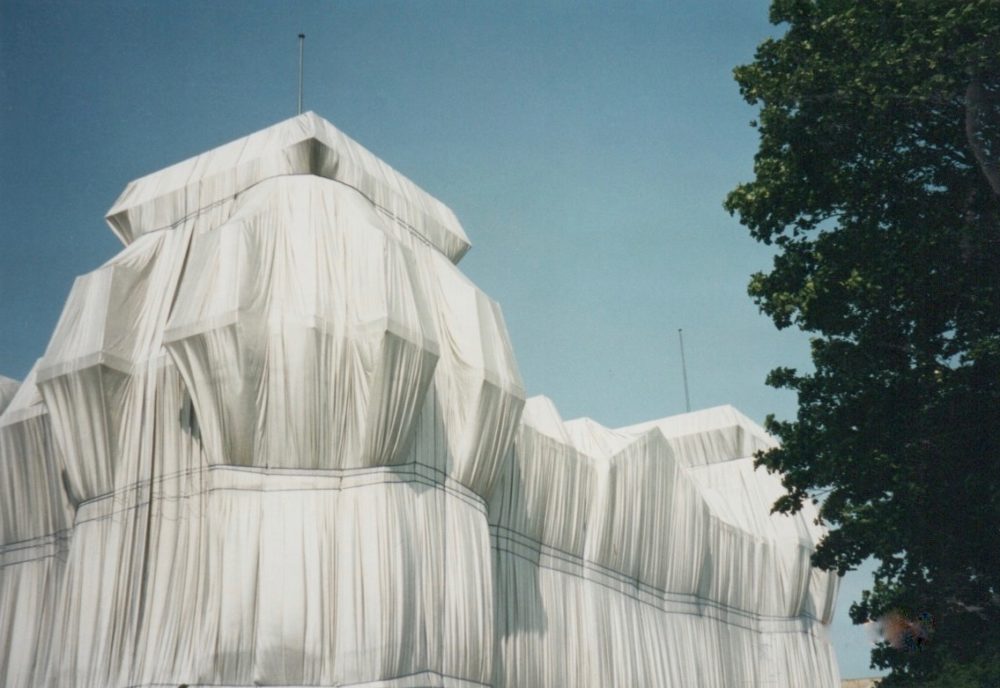

It took a workforce of 90 professional climbers and 120 installation team members 14 days to wrap the building, using 100,000 square meters of polypropylene and 9.7 miles of rope. Their meticulously conceived plan had been secretly tested with a full-scale mock-up at a castle near Hannover a few months previously. Taking copyright and trademark control to a new level, they rented the 1 kilometre piece of land surrounding the Reichstag in order to minimise use of their work as a backdrop for commercial purposes.

Over its two week life-span, five million people came to see Wrapped Reichstag. It was heralded as a supremely successful signifier for the reunification of Germany; its seductive, shimmering, ghostly form was reproduced in newspapers, magazines and TV channels across the world. People making the pilgrimage to see the work lounged on the grass in the summer sun, basking in a renewed sense of possibilities and a site transformed.

Members of Parliament, clearly relieved that the endeavour was so universally well-received, invited Christo and Jeanne-Claude to extend the project. The artists said no. When asked about their adherence to the two week life-span, Christo compared the temporary nature of the work to the tents used by nomadic tribesmen, quickly erected and equally quickly removed, and to the transience of life: “It is a kind of naiveté and arrogance to think that this thing stays forever, for eternity. All these projects have this strong dimension of missing, of self-effacement… they will go away, like our childhood, our life. They create a tremendous intensity when they are there for a few days”.2

In 1999, when the German capital and government moved from Bonn to Berlin, the Reichstag became the home of Germany’s parliament. It now serves as a symbol of the country’s reunification and is an architectural landmark in the city. The ghost of the wrapped Reichstag lingers on in the memories of those who saw it and, maybe more so, in those who didn’t.

Wrapped Reichstag was a twenty-four year-long lesson in ownership and control. As Christo said, “Everything in the world belongs to somebody”.3 He and Jeanne-Claude did everything in their power to work against a well-honed capitalist system that demands financial exchange and profit, by refusing sponsorship or government funding, and creating an experience that nobody could own, appropriate, or buy a ticket to experience. The blink of an eye time-frame defied the logic of the market and drove home the radical utopian nature of the endeavour.