When the Paleis voor Volksvlijt (rough translation: Palace of Popular Diligence) opened in Amsterdam in 1864 it was seen as part of a broader European celebration of the progress of industry and international trade, and the project of Empire as a whole. The design was based on London’s Crystal Palace, an enormous, state-of-the-art, cast iron and prefabricated plate glass structure built in 1851 to house the Great Exhibition in London’s Hyde Park.

In the early years, the Paleis voor Volksvlijt was used as a concert hall and when it proved to be unusable for exhibitions it became an entertainment centre and luxury shopping venue. It was destroyed by fire in 1929 and was finally torn down in 1960 to make way for the new Nederlandsche Bank building.

In 2016, James Beckett (an artist born in Zimbabwe, raised in South Africa, living in The Netherlands) reconstructed a fragment of the palace, taking his design from an archival photograph of a flank of the original building in a haze of smoke, taken just after attempts had been made to douse the flames with water. He installed his sculpture, Palace Ruin, in front of Amsterdam Zuid train station in the city’s financial district – home to the country’s largest banks, law firms and multinational corporations. This architectural environment has its roots in the glazed, shimmering world of nineteenth-century international exhibition centres such as Paleis voor Volksvlijt and Crystal Palace, and later, the aesthetics of modernism.

Like Paleis voor Volksvlijt, Palace Ruin housed performances, cultural programmes and exhibitions involving musicians, curators and artists. A programme of public talks tackled the subject of architecture, capitalism and decay, while inside the sculpture, Beckett presented his research into recent high profile corporate fires involving skyscrapers, arson attacks and defraud attempts. At various points throughout the day, the sculpture emitted smoke to echo the ruinous, smouldering state of the original palace. Alarmed passers-by were also confronted with a pungent smell of soot and ash.

A symbol of progress, technological advances, civic unity and pride is transformed into a signifier of fragility, loss and faded glory. Palace Ruin reflected the perilous state of global capitalism and the on-going, destructive legacy of Empire. Through its referencing of the grand architectural statements of the nineteenth century and their ultimate demise, it echoed the words of writer W.G. Sebald: ‘somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.’1 The programme of talks, exhibitions and concerts held within the sculpture offered a potential path to another route involving creativity, community, and conversation.

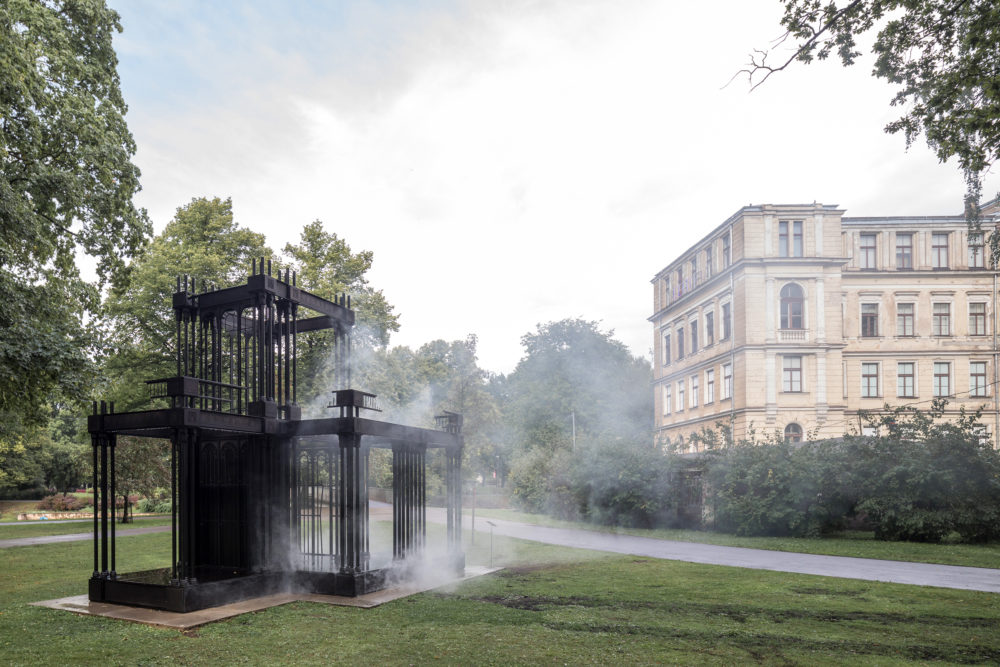

Palace Ruin was included in the Riga Biennial, Latvia, in 2018, where it was installed in Kronvalda Park, a very different environment from corporate, urban Zuid, and one which harked back to the parkland surrounding Crystal Palace and Paleis voor Volksvlijt. Beckett and curator Katarina Gregos positioned Palace Ruin within the historical, political and economic conditions of Riga and the tensions that exist between Latvia and Russia, alluding to the move from communism to capitalism and a questioning of the neo-liberal project.

A year later, Palace Ruin was installed in Wuzhen, east China – a picturesque village created for tourists, often dubbed ‘China’s Venice’ due to its extensive system of canals and waterways. An entirely constructed reality in which traditional architecture sits alongside state-of-the-art facilities, it is difficult to ascertain what is ‘real’ and what is not. Positioned amongst this spatiotemporal confusion, Palace Ruin took on a new altogether more surreal palimpsest of histories.