The 1987 iteration of Skulptur Projekte Münster (SPM) included the installation of a life-size yellow plaster replica of the Lourdes Madonna in a busy pedestrian shopping street. This was the work of German artist Katharina Fritsch who had a long-standing interest in devotional objects, particularly those that reference the apparition of the Virgin Mary in Lourdes, France in 1858.

Five years previously, in 1982, Fritsch had created Madonnenfigur (Madonna Figure), a small, hand-cast bright yellow multiple. The work was produced in an unlimited edition and began a discussion about the relation between art and souvenir objects, and the position of art within a market economy. The sculpture she produced in Münster was a re-imagining of Madonnenfigur, involving a much bigger, public stage.

Made of duroplast resin, the Madonnenfigur for Münster was coated with a luminous yellow enamel, a finish that placed it firmly within the language of mass-production and kitsch. Unlike many statues and monuments scattered across European towns and cities, the artwork was not elevated on a plinth or situated in a designated civic site but was installed flush with the ground in a busy shopping street between a department store and a Dominican church. Most adults passing the sculpture could look the Madonna in the eye.

SPM curators Kasper König, Britta Peters and Marianne Wagner must have had a hunch that the exposed setting, as well as the schism between the visual aesthetic and subject matter of the work, rendered it vulnerable to some form of ‘interaction’. It is unlikely, however, that they foresaw the relentless nature of this violence and the sheer number of attacks that were carried out on the work over its six month installation in the town centre.

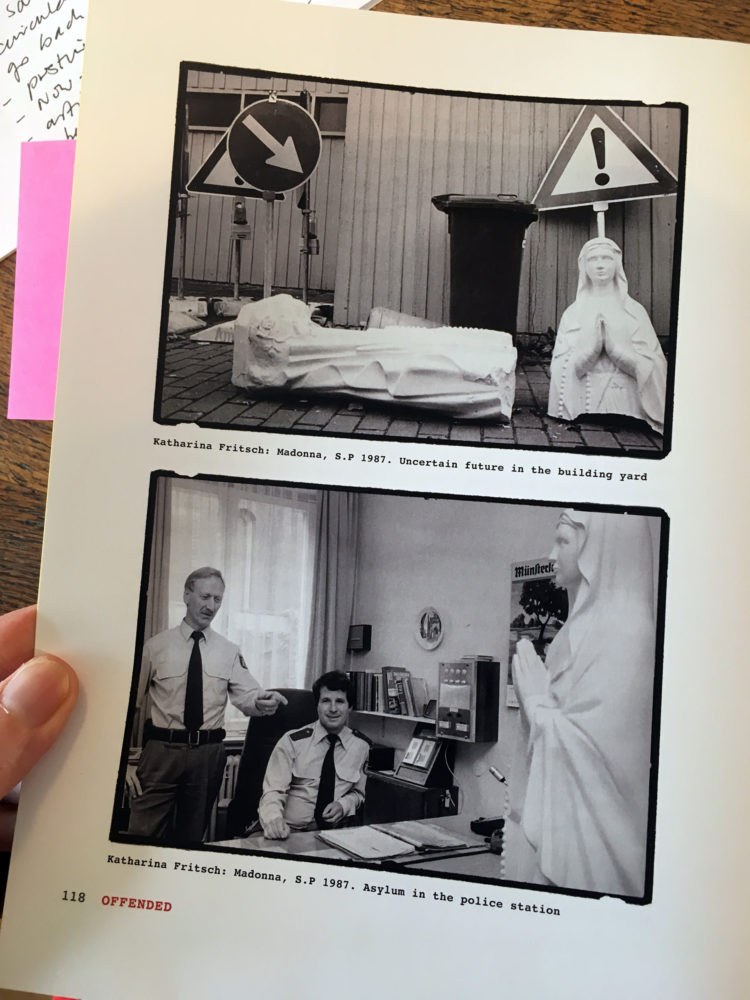

On the night of the 12 June 1987, a few days after it had been installed, an attempt was made to extract Madonnenfigur from its location and make off with it. A student working for SPM happened to be nearby and reported the incident to the authorities. The work was taken into ‘safe custody’ at a local police station.

Two days later, Madonnenfigur had been repaired and was reinstalled, this time anchored more securely to the ground. The next night it was smashed with heavy tools or hammers.

Residents expressed their concern in the local paper:

It is important that Germany’s most beautiful city remains a talking point in relation to events like this. Therefore, all the more regrettable is the incident with the yellow Madonna […], especially because it was a piece of art in the proper sense. However, gross negligence must be attributed to those who were responsible for the statue being placed at this particular location. The severe damage to the statue was absolutely foreseeable.…they want to force us […] to deal with modern sculpture in the most unusual places…the Madonna looked lonely, helpless, […] and is exposed to the people’s disdain.1

Madonnenfigur was remade, this time in a more durable material, and reinstalled in August. It wasn’t long before her nose was broken, her eyes were scratched, and she was daubed in graffiti. “This sculpture certainly is rather provocative” said a representative from the Landesmuseum.2

Towards the end of August, Madonnenfigur was decapitated and lay in fragments in the carpark of Münster’s cleaning services. In September, the work was repaired and reinstalled for the fourth time. It was placed under police surveillance and future attempts to damage or remove it were foiled.

Commenting on the contrasting way that Madonnenfigur was treated during the day and night, Fritsch said “People got very emotional. In the daytime, people brought candles and flowers and stood there singing and taking photographs. Then in the night, drunken people hit her or sprayed her. I never expected anything like it”3

The image of the Lourdes Madonna is a widely recognised, universally understood signifier of Catholic devotion. Speculation about the role that religious belief systems played in the relentless destruction of Madonnenfigur played out in the artworld, local community and press. Why, in this predominantly Catholic town, would people choose to destroy, damage and steal a representation of the Virgin Mary? Were they affronted by the kitsch treatment of their Lady? Was some of this aggression a result of its perceived ‘availability’ – its democratic positioning and physical relation to the public? Can we presume that it was predominantly women who laid flowers at Madonnenfigur’s feet, and men who abused her? Sexuality, misogyny, and posturing are all themes that Fritsch has developed over the course of her career, often in fantastically bold ways. In 2013, she installed a huge bright blue cockerel on the empty plinth in Trafalgar Square, London, and called it Hahn/Cock.

At the end of SPM 1987, Fritsch’s Madonnenfigur passed into the ownership of the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation in Toronto, Canada. Today, it is part of the Gladstone Collection in New York, USA.