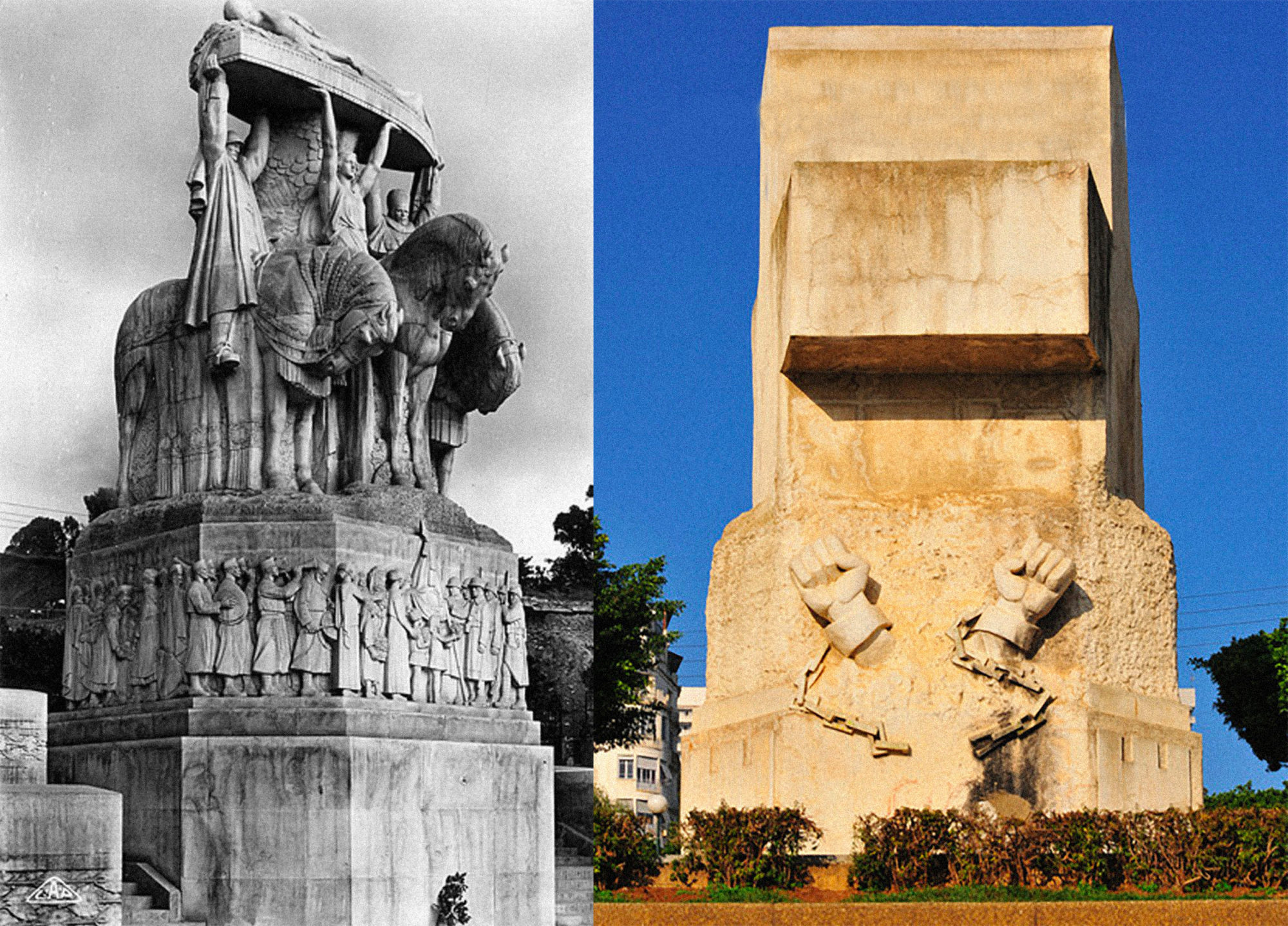

Enclosed by Algerian artist Amina Menia revisits the history of a monument located in the centre of Algiers. Paul Landowski’s Monument to the Dead was commissioned in 1928 by French authorities to commemorate French and Arab soldiers who died in World War I. The expressed intention was to show the close ties that existed between the people of Europe and Africa, a sentiment most evident in the group inscribed on the back of the monument. ‘The two women, the two old men, the European and the Arab lean on one another. The unity of emotion created a happy visual effect,’ Landowski wrote in his journal in 1921. To Algerians, the monument was a celebration of their subjugation and a painful reminder of on-going colonial oppression.

During the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962), the monument became a focal point for protests and public expressions of frustration about the progress of the war. Sixteen years after independence tolerance for the monument ended. In 1978 as the city prepared for the Pan African Games, an agreement was reached that it should be removed or destroyed. One of the founders of Algeria’s modern art movement, artist M’hamed Issiakhem led a campaign to allow Issiakhem to reclaim this physical manifestation of Algeria’s colonial past by encasing it in a new memory of Algeria’s socialist revolution.

The irregular shape of Landowski’s original monument is echoed in Issiakhem’s bulging Brutalist monolith, a reminder of what remains entombed under the surface. The featureless abstract nature of the structure is dramatically ruptured by the inclusion of two powerful fists, breaking free from their chains. As historian Henry Grabar has written, Issiakhem’s monument derives its power from its ability to both recognise and defy history:

Issiakhem’s piece speaks to the deeper political truth of post-colonial identity: the past, however painful, must be acknowledged as the foundation of certain aspects of contemporary society. It clashes with the National Liberation Front’s desire to eradicate all vestiges of colonialism. Art allows a narrative complexity that defies the simplicity of official texts.1

In 2012, during the celebrations for the fiftieth anniversary of Algeria’s independence, a crack appeared in the outer sarcophagus which then began to crumble. Sections of the original sculpture, including faces and limbs, began to appear; the monument was quickly shrouded in scaffolding and repaired.

For her Sharjah Biennial 11 installation in 2012, Algerian artist Amina Menia repositioned the memorial as a ‘double monument’ – a metaphor for the complex and fraught Algerian-French relationship.2 A debate has since developed between those who want to keep the shell and those who want to remove it. In a text accompanying the exhibition, Menia stated:

As a representative of the third generation of artists to deal with this memorial, I have chosen to place the works of the two artists in dialogue. M’hamed Issiakhem was obliged to cover the original monument, but he offered us the choice – or perhaps, the responsibility – to accept or reject it. Reflecting on this gesture, I highlight unseen details, creating links where only dots were left.3Enclosed is the story of the legacy of empire, the need to recognise the wrongs of the past, and the cracks in the system, told by three generations of artists, representing three different artistic genres (social realism, modernism, and conceptual art) in dialogue with each other.