From the moment it was installed on a small green in Cambridge town centre, Barry Flanagan’s Cambridge Piece was vehemently disliked by locals and students. Commissioned as part of the UK-wide Peter Stuyvesant Foundation’s City Sculpture Project of 1972, the work consisted of four, five-meter high totem pole-like structures and a steel frame. It was due to remain in place for a period of six months.

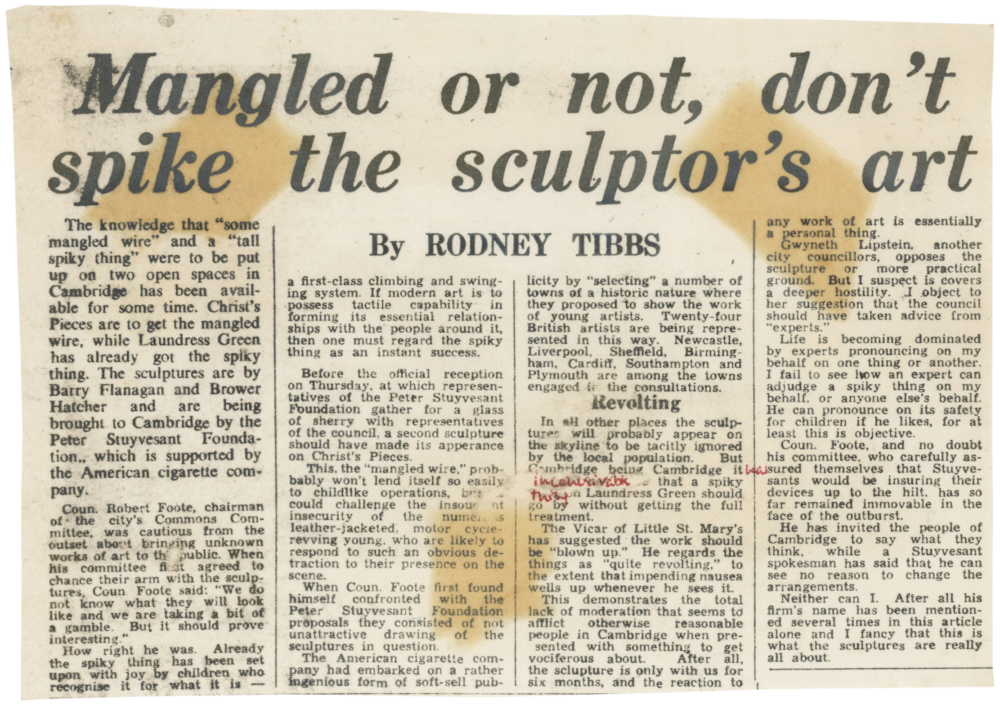

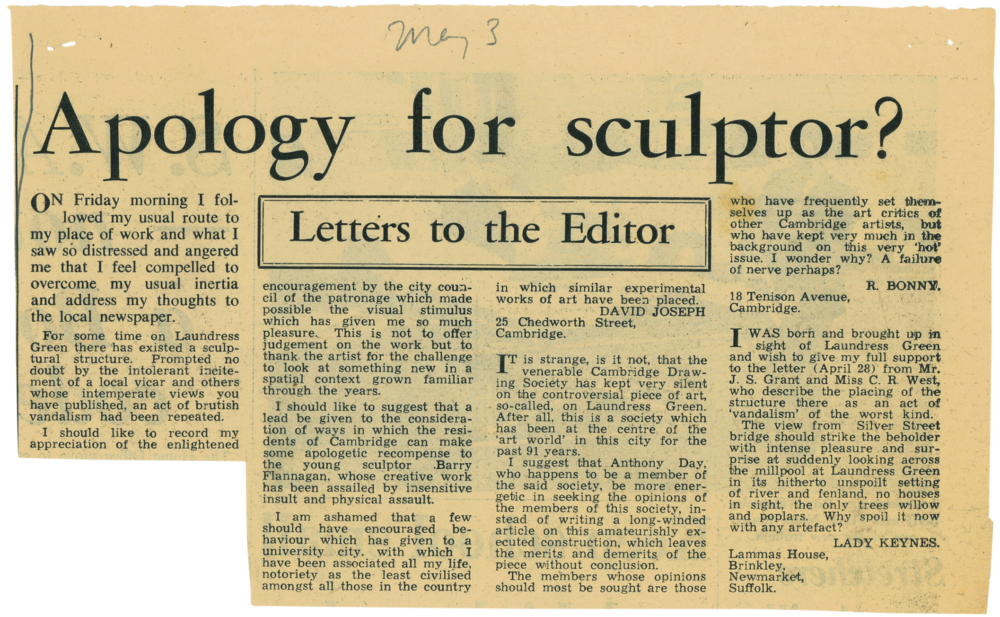

An outraged vicar wrote to the local press demanding that the sculpture be blown up on the grounds that ‘impending nausea wells up’1 whenever he walked past it. An article entitled ‘blow up revolving art’ followed; the term has been joyfully appropriated by public art sceptics ever since. A barrage of press articles began by decrying the aesthetic qualities of the sculpture and later provided accounts of the various acts of ‘vandalism’ that led to the work’s removal only two weeks after its installation.

Made from plastic, sand, canvas and iron girders, the work was vulnerable to damage. A washing line, replete with dirty clothes, was strung across the totem poles (a pleasing nod to the park’s name: Laundress Green) and a toilet seat was installed on one of the columns along with some artfully arranged bits of toilet paper. Kids adopted the work as a climbing frame and dogs contributed to the clamour by pissing on the poles. A newspaper reported that Flanagan addressed this issue by placing ‘dog repellent around his controversial sculpture’.2

Local resident Irene Seccombe launched an excoriating attack on the work in the local paper, decrying the desecration of the bucolic landscape:

Into the midst of this peaceful scene have now been cruelly bored four grotesquely contorted steel columns covered in plastic … of a hard bluish-green colour, calculated (?) to clash as painfully as possible with all the live, ever-changing greens of the surrounding grass and trees, which are now destined to form a background to these sinister erections.The insensitivity of the Philistine body responsible for this outrage must antagonise every Cambridge citizen who possesses the smallest modicum of aesthetic sense, love of nature, or atmospheric awareness. Let us do all we can to have these atrocities removed as speedily as possible and let us be on our guard to ensure that they and their kind are not allowed to proliferate in Cambridge, lest we awake one morning to find ourselves in Disneyland.3

A counter argument was made by David Joseph of Chedworth Street who wrote to the editor to thank the city councillors and the artist for their role in the project:

I should like to record my appreciation of the enlightened encouragement by the city council of the patronage which made possible the visual stimulus which has given me so much pleasure. This is not to offer judgement on the work but to thank the artist for the challenge to look at something new in a spatial context grown familiar through the years.4Jeremy Rees, curator of the City Sculpture Project, appealed to critics to be patient in their demands for its removal, and allow members of the public time to get used to the work: “By putting it up for six months one might modify one’s views about it” he said. 5

Flanagan was keenly aware that the introduction of this playfully cajoling artwork into the landscape of a deeply conservative university town would result in some form of outrage. He dealt with his detractors using the logic of conceptualism, no doubt causing more consternation. When asked about its meaning, he said that the work (that remained nameless) “… has no intended meaning any more than a particular architectural feature of a building has any meaning. It works as a piece of sculpture …it will show this visually as architecture does and like trees and rivers do.”6

Flanagan’s irreverent approach to art-making, which included the extensive use of anti-monumental, non-durable materials, often resulted in works that confounded the status quo and elicited violent reactions. In 1967 he installed a series of three-meter high, three-ton sculptures made from sand and hessian on Holywell Beach in Cornwall which were destroyed by soldiers out on manoeuvres. A few years later, working with a similar, wilfully absurdist aesthetic, Flanagan made his infamous Bollard Project (1970) which formed a protest against Camden Council’s policy of installing a large number of permanent bollards on public pavements. A short grainy film shows the artist in full-blown gorilla-action mode, cutting up bits of blue canvas on the pavement, sewing sections together in an Anderson shelter-type structure, mixing concrete in the street and installing a series of squat little sculptures that form a hilarious, antagonistic dialogue with the existing, officially sanctioned bollards. Evidently, they didn’t last long.