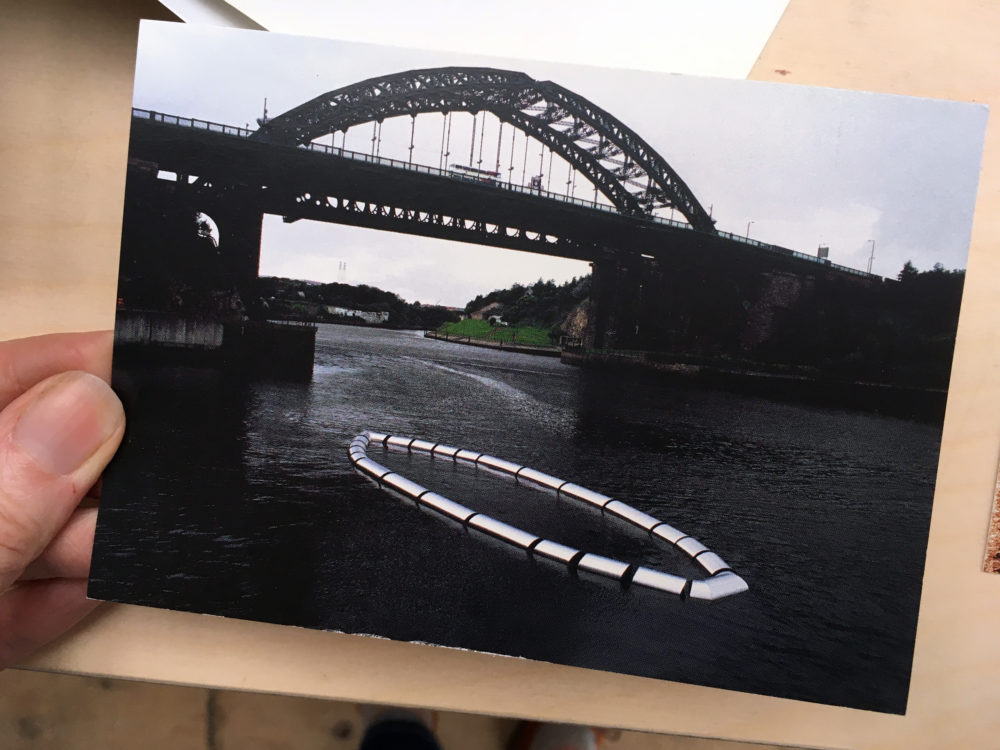

Alison Wilding’s sculpture Ambit was launched on the River Wear in Sunderland, northern England, to much civic fanfare in September 1999. Its elongated, flat oval form referenced Sunderland’s industrial past, and, more specifically, the thousands of boats that had been ushered in and out of the river, via Austin’s Pontoon, between 1903 and 1966. Weighing 22 tonnes and measuring 130 feet, Ambit was commissioned by Sunderland City Council to welcome visitors to the city. At night, the halo of light emanating from beneath the twenty-four stainless steel cylinders created a startling visual effect. By day, the cylinders reflected subtle shifts in light whilst constantly morphing to the push and pull of the river’s current. Located underneath the awe-inspiring engineering feat that is Wearmouth bridge, the work held a majestic, other-worldly place in the river, hinting at things below, unseen.

The Guardian announced that this ‘brave, audacious, beautiful’ sculpture had turned ‘Sunderland itself into a work of art’.1

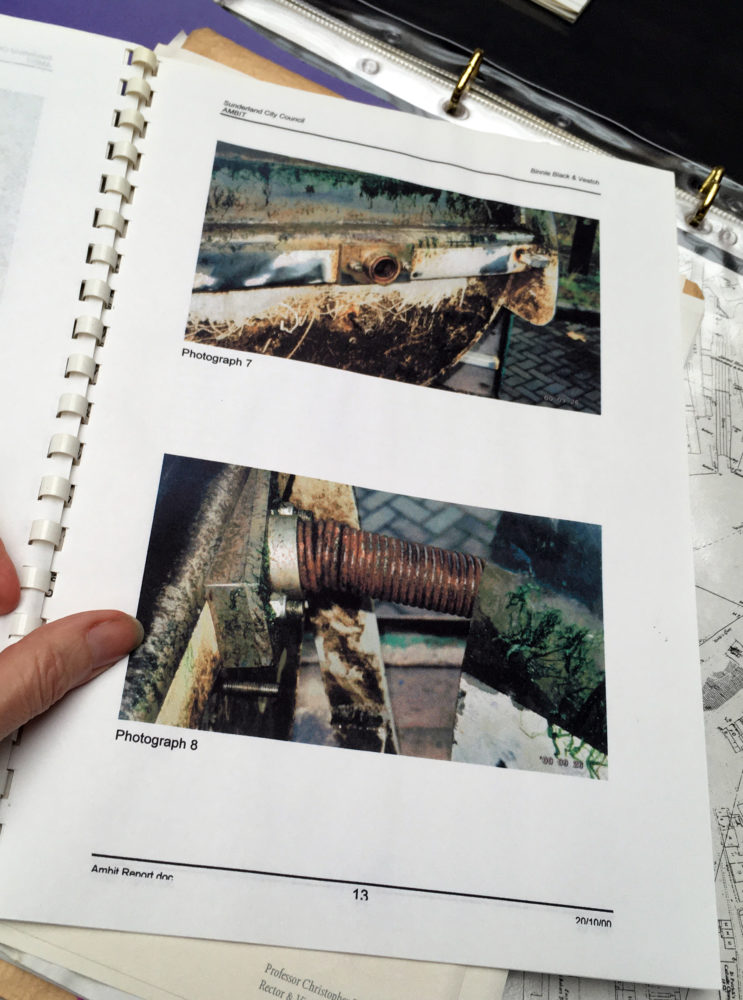

Within weeks of its unveiling, the lights began to fail due to a build-up of silt. In February 2000 the work was de-installed, taken for tests, repaired and returned to the water. Further damage caused by tidal movement, trapped river debris, as well as issues with the timer switch, continued to affect the work and the lights extinguished entirely within weeks. It soon became a target for local kids who hurled breeze blocks at it and severed its armoured power cables.

A national press furore ensued, the focus of which was often the £250,000 budget (raised through National Lottery and European Regional Development funding). Wilding was interviewed by Radio 4’s Today programme anchor man John Humphries, who delighted in the opportunity to display his antagonistic attitude towards contemporary art. The press gleefully reported the response of local people: “It’s not nearly as good as the Angel of the North.”; “It’s not likely to get vandalised in the middle of the river but it’s not very accessible.”; “I like it. I like modern art.”; “…our streets could have been paved with gold with the money wasted on this ludicrous venture.”2

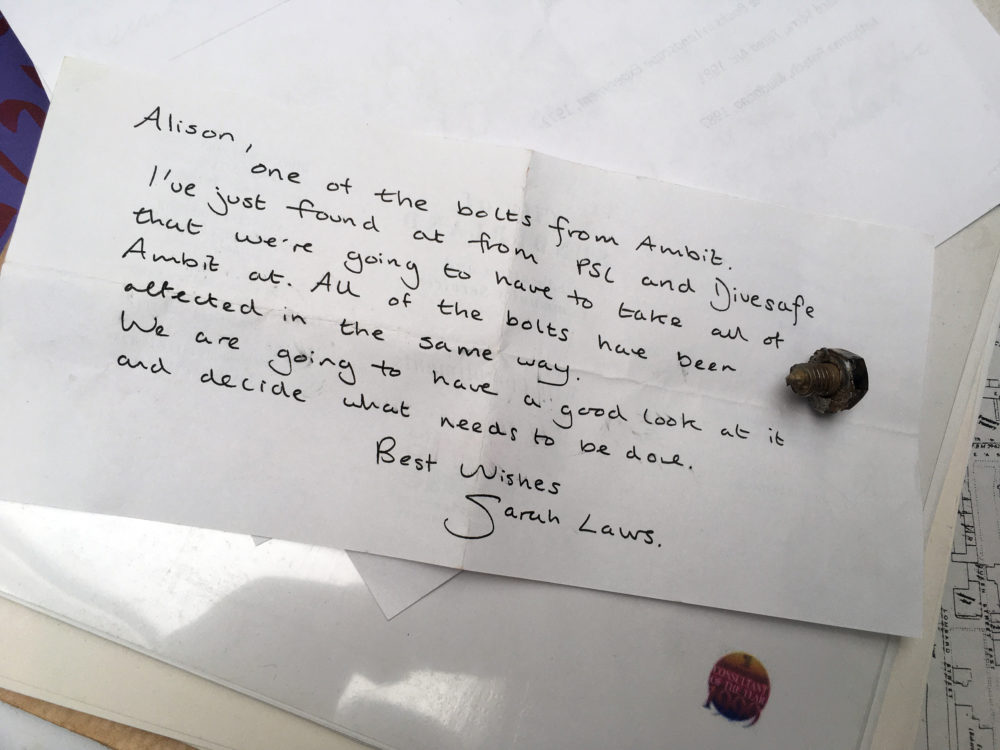

In September 2000, a year after it had first been installed, Sunderland City Council removed and dismantled Ambit and announced that it was going on tour to Venice, London, and other potential far flung destinations. The tour never happened but the work did make it to Manchester for the celebration of the 2002 Commonwealth Games. The sculpture was finally put into storage at the Sunderland Maritime Heritage Centre, a large question mark hovering over its future.

The story rumbled on and in 2006, when Wilding was interviewed by the local press, she said:

It’s a pity it’s in some lock up. Because it’s stainless steel, it would be much more use being sold as scrap. I’d personally have no objection were it to be broken up and sold for scrap, because I hate the idea of it being in some kind of elephants’ graveyard mouldering away.3In 2019, Wilding’s wish was granted and The Shields Gazette announced that Ambit had been ‘secretly scrapped’ and ‘sent for recycling’ in 2014. Nobody at the council made contact with the artist to let her know the fate of the work; Wilding had expressed a wish for the proceeds for any scrapping to go to the local art school. This is unlikely to have happened.

A work that was four years in the making, on public display for ten months, and in storage for fourteen years provides a cautionary tale for commissioners and artists. There were many contributing factors in the destruction of Ambit, including a lack of understanding about the physical conditions of a particular location (Wilding said the project team had failed to consider “the power of the river” and she took responsibility in playing a part in that failure); a breakdown of communication between council staff and contractors; a grandiose set of ambitions that were impossible to follow through; a lack of care over the narrative of the project – the relentless search for an ‘iconic’ artwork that would ‘define’ a city and attract tourists overpowered the contemplative, mysterious nature of the work.