How can wildly different publics be gathered around art? What form should this art take, and when a neighbourhood, culture, and identity is destroyed through gentrification and a ‘rush of the new’, how should it be remembered? Challenging the idea that a public monument should assume the form of an object in space, artist Nina Wakeford and curator Kiera Blakey discuss the ways that the histories and stories of the LGBTQ+ community and Flower Market staff in Nine Elms in South London in the 1980s can be memorialised.

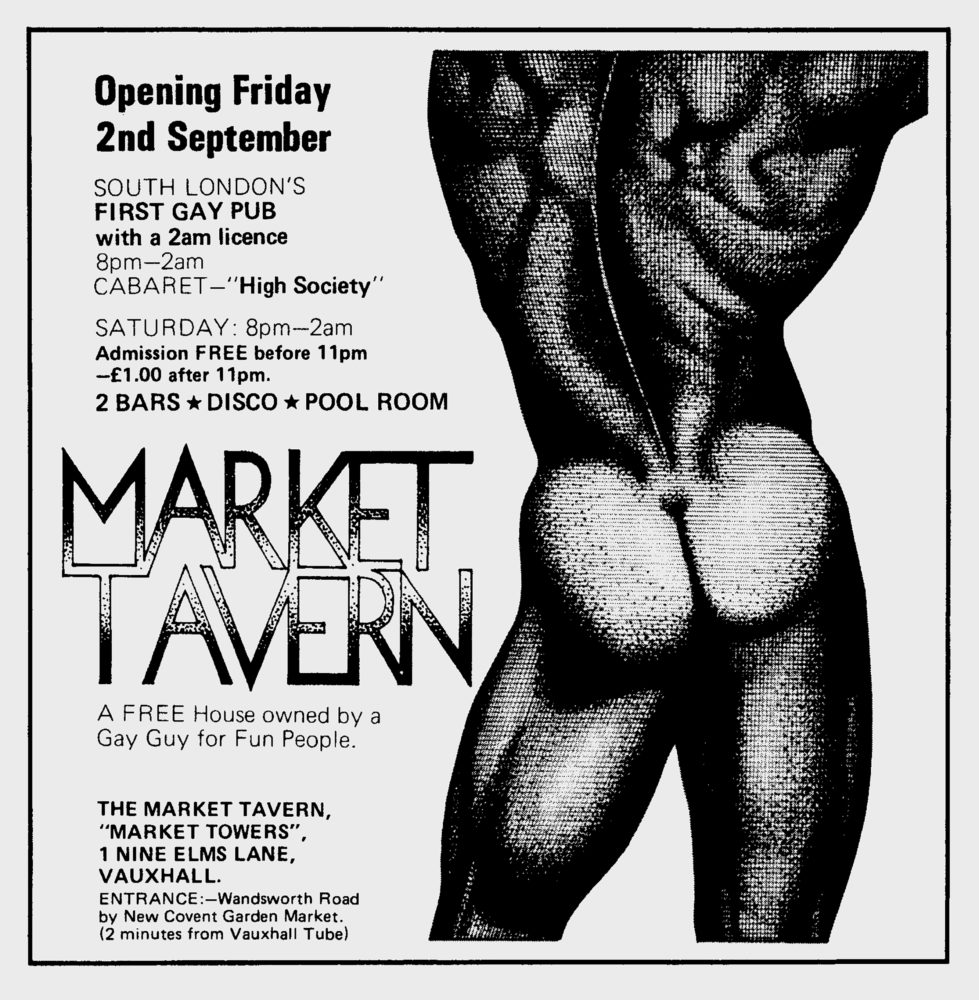

Kiera Blakey: Between 2016 – 2019, Nina and I worked together on a new public commission in the Nine Elms area of South London as part of Art on the Underground’s public art programme. It followed a two-year artist residency programme in the area, excavating the parallel counterpublics linked by the site, collecting stories and historical sketches in conversations with those working on the Northern Line extension, the LGBTQ+ staff who will operate it, as well as former patrons of the Market Tavern, a pub formerly located at 1 Nine Elms Lane, now demolished, like so many historic queer spaces in London, to make way for high-rise regeneration.

The impetus for the commission came from a Section 106 instruction as part of the development work underway to build two new London Underground stations: Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms. To walk around that part of South London is to enter a place becoming, a rapidly mutating landscape of furious construction, shiny buildings, ghostly avenues and empty shops. It’s not at a loss for public art either: works by Matthew Darbyshire, Amalia Pica and Sarah Lucas all live in this part of town, on the expansive plazas and new river fronts. They sit aside an enormous flurry of creative activity that attempts to forge links between communities and the public realm, while the enormous construction programme rages both above and underground. Nina’s resulting contribution took the form of a book, an oral history of the gay underground, published by Book Works.

When I invited you to make a public work I was really questioning the role of public art – what was it, who was it for, who gets to decide? I wanted to dematerialise the idea of the monument as the only conceivable and valid form of public art. How do you conceive of your practice in relation to these questions?

Nina Wakeford: When I studied for my BA in Art, which I finished in 2009, there were two orientations which I understood lacked sophistication: a desire to do public art commissions, and an uncritical interest in the monument. Even though I now appreciate the complexity of the debates about making art public and the dilemmas of monumentality, a part of me still carries around the idea that public art and the making of monuments is to be approached with extreme caution. This is rather paradoxical, given that my initial training in sociology gave me many tools to think critically about how the social world might be performed for a range of publics. And it clashed with my lived experience of histories which needed marking – I was very active politically in the midst of the AIDS crisis, as well as protesting Clause 28.

Looking back over the last few years, I realise that although I tell myself I’m trying to tackle the unfinished business of the 1980s through the making of art, I’m often also actively working out how publics are gathered around art – what needs to be held together, or pointed to, in public, as a monument might do. I’ve learned a great deal from the work of my former doctoral colleague at the Ruskin School of Art, curator Margrethe Troensegaard, who has pointed out that some monuments, named as such by artists, actively challenge the traditional view of monumentality. She cites Thomas Hirschhorn’s participatory sculpture ‘Gramsci monument’ (2013) as a case in point. Made of plywood and bits of tarpaulin, the work was constructed in a South Bronx housing estate. Visitors stumbled across a dispersed set of objects and populated spaces (a library, a stage, a newsprint office) that together formed a monument to an ex-leader of the Italian Communist Party and political theorist. Troensegaard insists that we have to consider the discursive function of such monuments, which position the viewer not as a receiver of messages but rather as participant in an ‘immersive encounter’. I’m always wondering if my work might raise such issues – of how and when we participate in a public scene or encounter.

KB: The central tenet of this work came from The Market Tavern, a pub formerly located at 1 Nine Elms Lane, now demolished, like so many historic queer spaces in London, to make way for the high-rise regeneration. Can you tell us about The Market Tavern and how you came to know about it?

NW: A friend and I almost went clubbing there when it was still in operation as a gay venue in the 1990s. But we never made it inside. I remember us driving down from Dalston to Nine Elms and bumping into a man coming down the stairs from the venue, and my friend asking ‘how is it?’ and him saying something to the effect of ‘rubbish’, so we headed off somewhere else. I didn’t encounter the Market Tavern again until I started research for the exhibition at Focal Point Gallery, and interviewed some members of a women-only motorbike group formed in the 1980s. They often met there – one of them had worked the door, and another had been a DJ. When I started the Art on the Underground project, I ended up tracking down a selection of people who had been there over two decades, including the original architect who told me all about the choice of ribbed concrete and the problems of piling so near to the Thames.

KB: The Market Tavern became the focus point of this project, a monument to a bygone era. Why is that important now?

NW: It was one of those research objects that proliferates in all kinds of directions and becomes more and more internally complex. I knew it first as a gay club, and there are many artists currently doing work on recovery of past queer spaces, such as Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlin’s atmospheric work ‘In My Room’ (2020). But I didn’t want to take the same approach. The Market Tavern couldn’t be revisited without acknowledging that the space was both a venue which housed various gay and lesbian themed nights within a whole Vauxhall ecosystem, and the site of after-work socialising for Flower Market porters and traders when they finished their night shifts at 5am. Having talked to several Flower Market ‘old-timers’, I realised that the sequential, and sometimes overlapping, use of the Market Tavern had to be reflected in the way I brought together histories in the making of the work.

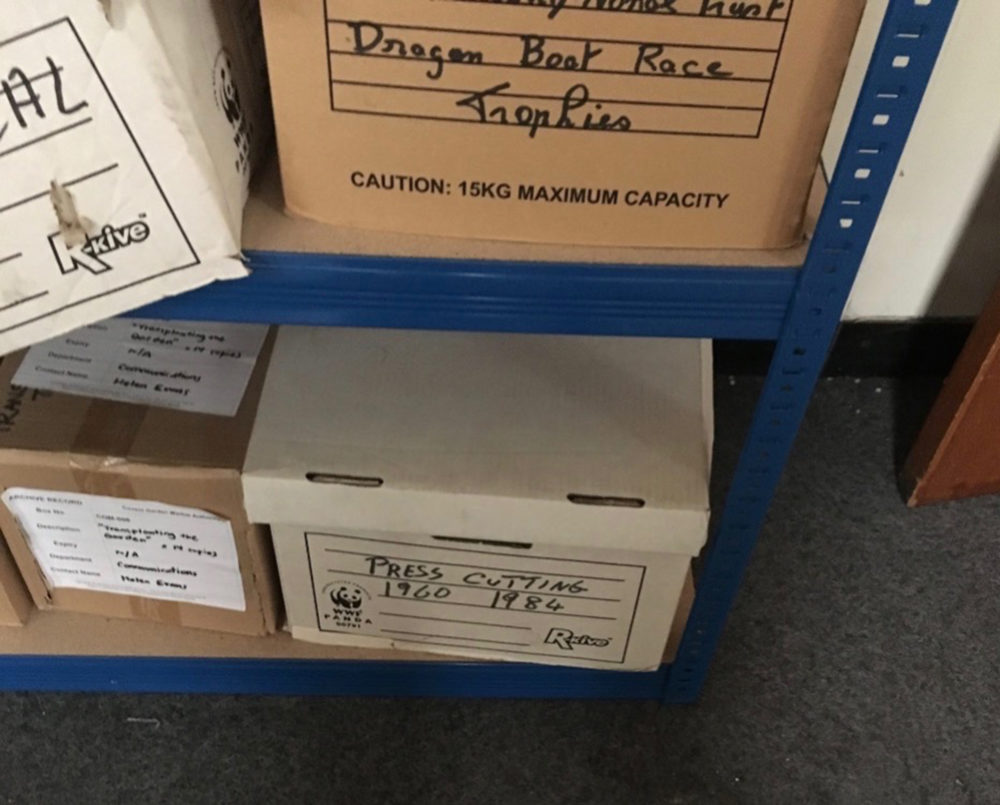

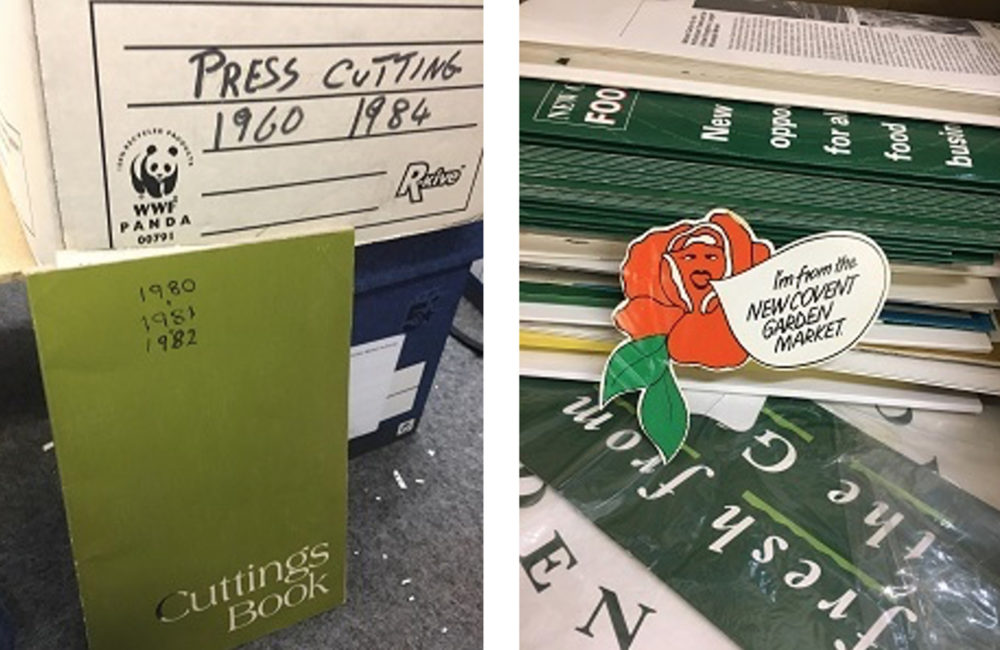

KB: One of my favourite memories with you was spending all day in an office atop the Covent Garden Market, which would have been very close to The Market Tavern. It was like the place where history was hiding, resting, hidden away and forgotten. There were boxes and boxes of archive materials, full of incredible photographs, scrap books and other ephemera pertaining to the time. There’s something so violent about all that history being shoved to the damp dark back of a building. How do you conceive of these colliding times? Why is it important to address this now?

NW: Swapping words under lockdown, it is almost unimaginable that we sat for so long together on the floor of that room, which I remember overlooked a huge expanse of chilly atriumed space, with just a single group of workers round a small table preparing and packaging fresh herbs, meticulously cutting and sorting. I agree, the room felt forgotten, but I didn’t think of it as violent, more as if the action was happening elsewhere. To me it was as if the rush of the new structures around Nine Elms, including the new Market buildings being built during that time, had left that whole 1970s concrete box behind, and the collection of photos and other bits of design and marketing ephemera were strangely at home.

KB: I think you’re right – not violent, just sad that all this memory was relegated, waiting to be lost. There was something fetishistic about rummaging through all that material, the old photographic papers, handwritten notes, the stale smell. In a sense you rescued so much of that material in the words and stories in your book. Can you say something about that, about the people, their lives and their stories as a form of public art remembered in a book as opposed to a shiny memorial? I’m interested in the shift of quality from the object itself and what we sometimes call ‘old genre public art’ to the quality of the temporal experience you created.

NW: I’ve been influenced by Elizabeth Freeman’s idea of temporal drag – which is a way of thinking through non-normative experience of time and its excesses and incompatibilities. The book allowed me to bring together lots of seemingly disparate accounts and propositions. It begins with an image from the Northern Line drivers’ handbook. The page reproduces, at 1:1 scale, a line diagram which drivers would recognise from current operating procedures, but which I’ve annotated in pencil to show the two future stations. I talked to many LGBTQ+ Northern Line drivers as part of the project, and wanted to recognise that it was their workplace – the new Underground tunnels – which I was filling up with histories and calling it their new Pink Depot. The spoken words of drivers are included in the text, along with those of DJs, clubbers, Flower Market traders, porters, engineers, miners and all those who in some way could be said to have occupied the site of the Market Tavern – above and below street level. I also went to East Tilbury in Essex where all the ‘muck’ extracted from the tunnels had gone. I was very moved by the willingness of everyone to keep an open mind as to what art might do in this context and I had a huge amount of help over nearly two years getting access to the live building site. The access and generosity of spirit, particularly of the miners, engineers and rail laying teams, helped me develop the posters for the Underground and the final live performance at Matt’s Gallery which happened on the night of the book launch in November 2019.

KB: Why do you think it was important to remember people in this way? Do you have any final thoughts on what gets lost and what gets left behind? And about this destruction of communities and personal histories?

NW: It was important that people could recognise themselves – sometimes verbatim – as they encountered the text and images in the final publication, or when they saw the posters on the Northern line, or heard the performance. By juxtaposing words largely derived from transcripts, I hoped to offer the suggestion of interchanges – which have never actually taken place – between worlds and experiences and eras. By starting each photo section with a picture of the curly metal ‘clip’ which attaches the rail to the tunnel, I wanted to remind the reader that this was part of complex infrastructure project that involved many components – yet in the end was also a railway. Each of those clips along the line was hammered in by one of the overnight rail ‘gangs’ with whom I spent time. Part of how I remember them all is through respeaking their words myself, in a live performance, and my ‘lessons to self’ which are written out in the book to propose some methodological ‘tricks of the trade’ in voicing what I had learned. I’m not sure I really built a monument in Troensegaard’s terms. In order to finish the project I had to leave lots of words and experiences behind. Although the project started with a site in Nine Elms which was, as you say, in a ‘furious’ state of construction, what kept coming back was the way in which each of the communities or groups with whom I interacted had their own relationship to processes of what was new or to come, and what had been removed or destroyed. The architect of the original Market Towers was not at all sentimental about the building itself coming down as it had facilitated his career as a very young graduate and he went on to manage significant projects around the world. Responding to my questions enabled him to reconstruct anecdotes about the farcical opening day when the Queen had to be guided to the one working lift which stopped at the one finished floor! For many of the gay male drivers, the impact of AIDS on the London Underground in the 1980s was a far more significant event than the removal of one particular club, and yet they mourned a place-based community ethos which has been replaced by social media and dating/hook-up apps. These losses run through the words in the scripts, mostly as memories, and are interleaved with the accounts of building the new railway.