The Futurist movement’s ‘anti-neutral’ suit was designed to incite violence and pro-Fascist activity. Artist Eloise Hawser tells the strange story of its first and last outing, its destruction, and the paradoxes embedded within its making.

By 1914, Italy’s Futurist movement had already drawn up a number of manifestos that insisted we forge new relationships with everyday items, ranging from clothing and architecture, to cooking and children’s toys.

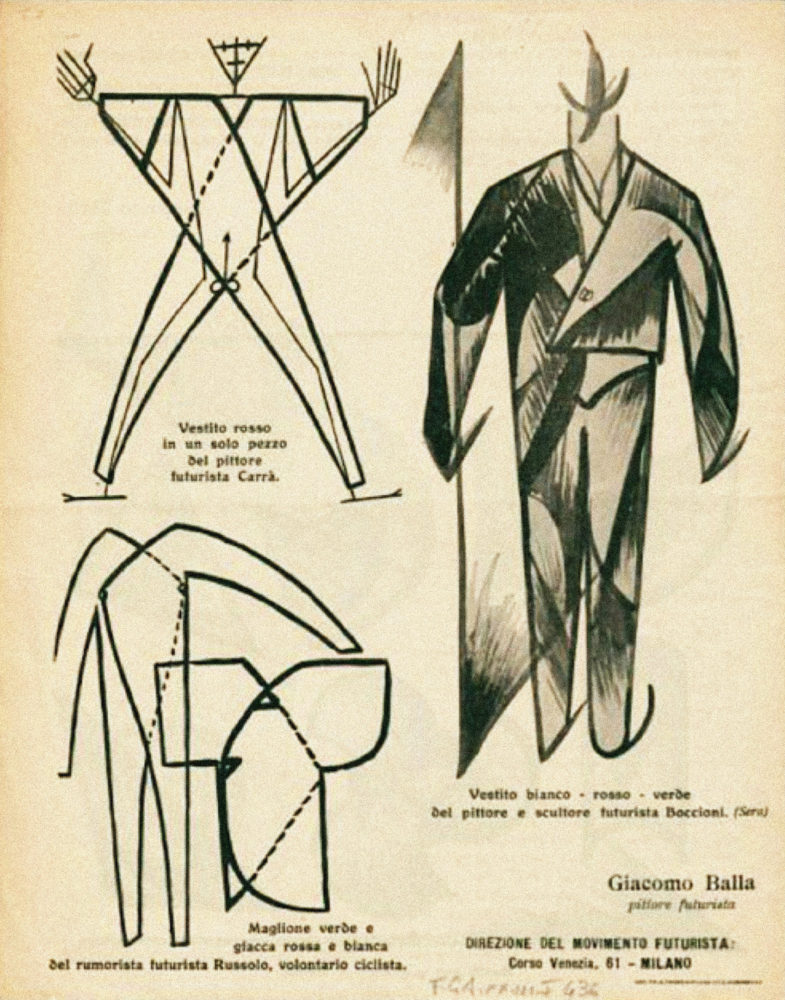

In his The Anti-neutral Suit: Futurist Manifesto, poet and designer Giacomo Balla calls for a peculiar, wrap-around garment designed with aggressive patterns called ‘force-lines’ in the red, white and green of the Italian flag, complete with a matching tricolour beret. The aim was to turn its wearer into a ‘human flag’ and incite the Italian public to join the side of Germany in pursuit of a violent, nationalist politics. As Balla wrote in 1914:

We Futurists want to liberate our race from every neutrality, from fearful and enervating indecision, from negating pessimism and nostalgic, romantic, and flaccid inertia. We want to color Italy with Futurist audacity and risk, and finally give Italians joyful and bellicose clothing.1Balla designed three ‘bellicose’ suits; one for himself, one for poet and Futurist leader Filippo Marinetti, and one for fellow poet Francesco Cangiullo. The suits were to be revealed at Rome’s Institute for Civil Law on 11 December 1914, in the middle of a student lecture given by eminent professor Giuseppe Chiovenda, whose views the Futurists considered ‘neutralisti’ and ‘tedescofili’ (neutralist and pro-German). Earlier that year, future leader Benito Mussolini had issued a rallying cry for Futurism, writing in a magazine, ‘Neutrals… have always gone under. It is blood which moves the wheels of history!’2

When the day of the lecture arrived, however, Balla had only managed to complete one of the three men’s suits. It was agreed that Cangiullo would have the honour of unveiling the garment, hiding it under his ‘loden cape’ as though it were a dangerous weapon before revealing it to the students. Cangiullo, flanked by Marinetti and Balla, describes the unveiling with characteristic hyperbole:

We force our way through, slamming into the lecture halls. The students rear up, the professors try to escape like the inhabitants of Troy… The bells are ringing. The janitors come running like firemen. Alarm: ‘Throw them out!’… Bottles are smashed between the rage of our opponents and the exultation of our sympathisers. The most impetuous moment is here! The most lyrical! The least philosophical! Bristling with clenched fists and torn-open mouths,… I unbutton my cape in one rip, pull out the beret: from under the skin of my Loden cape escapes a human flag.3This was first and last outing of the suit. After violent altercations with the students, the suit, in Rose Sydney Parfitt’s words, was ‘destroyed by the force of its own impact’.4 Cangiullo has a fabulous description of this moment:

But before my certain combustion, I had a chilly surprise. Right there in the street, I feel and find myself to be all but naked. The tricolour jacket vanished along with the beret, trousers in tatters, the buttons missing, the braces hanging. I believed myself to be the lover of Italy caught in the act.5There are a number of curious paradoxes here. On the one hand, the Futurist suit is designed to incite chauvinism, violence, and warfare. On the other, it is so lightweight and dandyish that it fails to withstand its first public outing, being shredded by a ruckus with students. There’s also the fact that the suit was made by a female workforce. After struggling to find a suitably dexterous tailor, it was sewn by Balla’s daughters, Elica and Luce, whose use of traditional, often highly gendered, handicraft was a far cry from the industrialised, androgynous processes celebrated in many Futurist poems and projects.

Cangiullo navigates these paradoxes in a wonderfully masculine fashion: treating the suit as though it were a sacrifice to conflict, he feels as if he were the vindicated, hyper-macho lover of Italy even in the midst of his suit’s ‘combustion’.

Naturally, the students did not object to Cangiullo’s outfit on the grounds of fashion. Rather, they objected to the kind of politics that it sought to proselytise. This gives us yet another paradox: insofar as the Futurists wanted their suit to incite conflict, technically-speaking, they succeeded. And, given the vigour with which the students answered this call to arms – albeit from the opposite end of the political spectrum – the Futurist suit reveals how political energies are invested in inanimate objects and materials. From Cangiullo’s depiction of the incident, furthermore, these political energies are mistaken for the ‘power’ of the suit itself. What would it mean, in this light, to archive a material defined by its political investments, especially when no traces of this material survive?

When Jes invited me to contribute to the Archive of Destruction (a delicious oxymoron), I immediately thought of the Futurist suit. Destruction was a key register for the Futurists, for whom it represented both a liberating assault on the old order, and the freedom to imagine a wholly new future. It also involved the destruction of a particular form of memory. In the words of The Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (1914):

Let us call a halt to monumental, funereal, commemorative architecture. Let us blow up monuments, pavements, porticoes, stairways and sink the streets and piazzas, elevating the level of the cities.6The Futurists’ attack on the past was exhaustive. Not only was commemorative architecture a target, but so too was ‘passéist’ clothing, as is evident in these excerpts from the Futurist Manifesto of Men’s Clothing, written by Balla in 1913:

WE MUST DESTROY ALL PASSÉIST CLOTHES, and everything about them which is tight-fitting, colourless, funereal, decadent, boring and unhygienic … Let us finish with the humiliating and hypocritical custom of wearing mourning. Our crowded streets, our theatres and cafés are all imbued with a depressingly funereal tonality, because clothes are made only to reflect the gloomy and dismal moods of today’s passéists.7 One thinks and acts as one dresses. Since neutrality is the synthesis of all tradition, today we Futurists display these antineutral, that is, cheerfully bellicose, clothes.8The intensity with which the Futurists invested their political energy in everything from clothing to architecture should come as no surprise. For them, the material world was already saturated with these investments, it was just saturated with the wrong ones; the humiliating, the hypocritical, and the passé. For Marinetti, Balla, and Cangiullo, destroying vessels for these investments was a ground-clearing exercise from which Futurist ideals could emerge and take hold.

It seems to me that the Futurists would have hated the idea of being archived. Not only would they be sharing a space alongside artefacts that they would no doubt object to, from passé clothing to commemorative architecture, but because archiving, as an act of preservation, establishes a continuity with the past. It is precisely this continuity that they sought to destroy. If the Futurist suit, therefore, can be inducted to an ‘Archive of Destruction’, then it paradoxically does so as an emblem for a ‘destruction of the archive’.